January and February – Seeds of Rebellion Part Three

From colony-wide to county-wide, the seeds of rebellion had been planted and were beginning to sprout…

The Birth of Rebellion: North Carolina’s Revolutionary Spirit in the 1700s

In the Carolina backcountry of the 1770s, far from the established colonial centers of Boston and Philadelphia, a revolutionary fire was kindling that would challenge the traditional narrative of American independence. Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, became an unlikely crucible for patriot sentiment, where Scots-Irish settlers, Presbyterian ministers, and frontier farmers forged a distinctly Southern brand of resistance to British authority. Understanding how this remote region developed such fierce independence requires examining the unique cultural, religious, and political factors that transformed loyal colonial subjects into America’s earliest self-proclaimed revolutionaries.

The Scots-Irish Legacy: Seeds of Defiance

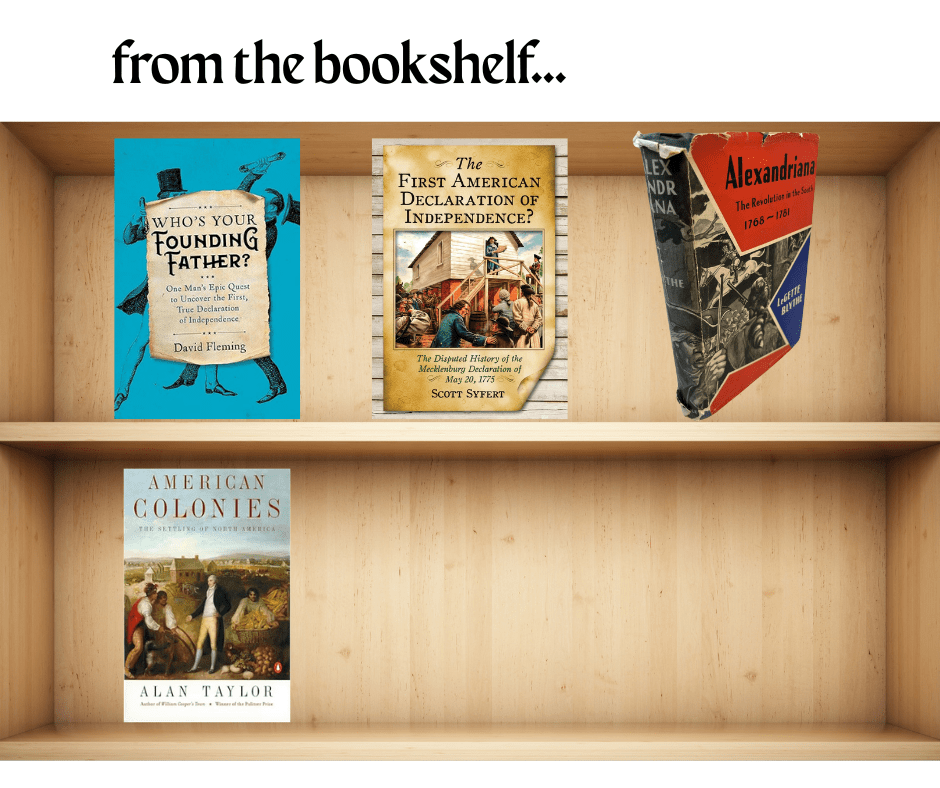

The foundation of Mecklenburg County’s patriot mindset was laid long before the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord. The region’s predominant settlers were Scots-Irish Presbyterians who brought with them a bitter legacy of religious persecution and political marginalization. These immigrants had already endured discrimination in both Scotland and Ireland, where their Presbyterian faith marked them as outsiders in Anglican-dominated societies. As historian Alan Taylor notes in American Colonies, the Scots-Irish carried “a fierce independence and distrust of distant authority” that would prove combustible when transplanted to the Carolina frontier.

This cultural inheritance was not merely abstract resentment. The Scots-Irish settlers had concrete experience with oppressive governance, making them particularly sensitive to perceived injustices from the British Crown. When they established communities in the North Carolina backcountry during the mid-1700s, they brought these memories with them, creating a population predisposed to question and resist overreach by distant powers. Their Presbyterian church structure, which emphasized congregational governance rather than hierarchical authority, reinforced democratic ideals and collective decision-making that would later characterize their revolutionary activities.

Religious Grievances and Colonial Betrayal

The transformation from grievance to open resistance accelerated when the British Privy Council in London dealt Mecklenburg’s settlers a stinging betrayal. After supporting Royal Governor William Tryon against the Regulator movement in 1771 – a costly decision that pitted backcountry settlers against each other – the Scots-Irish Presbyterians of Mecklenburg expected recognition and reward for their loyalty. Instead, the British government voided colonial legislation that had granted them crucial rights: the establishment of Queen’s College (which would have provided local higher education) and the legal authority for their ministers to perform marriages.

This duplicity struck at the heart of the community’s identity. Education and religious legitimacy were not peripheral concerns but foundational elements of Scots-Irish Presbyterian culture. The revocation represented more than administrative inconvenience; it was a profound insult that confirmed their suspicions about British indifference to colonial needs and rights. As Scott Syfert documents in The First American Declaration of Independence, this betrayal “further alienated the community from British rule” and provided tangible evidence that loyalty to the Crown would never be reciprocated with genuine respect or representation.

The Princeton Connection: Intellectual Foundations

While cultural predisposition and political grievances created the emotional fuel for rebellion, intellectual justification came from an unexpected source: the College of New Jersey at Princeton. Several key figures in Mecklenburg County’s revolutionary leadership had studied at Princeton, including members of the prominent Alexander family. The college, under Presbyterian leadership, was a hotbed of Enlightenment thinking blended with Reformed theology, producing graduates who could articulate sophisticated arguments for natural rights and limited government.

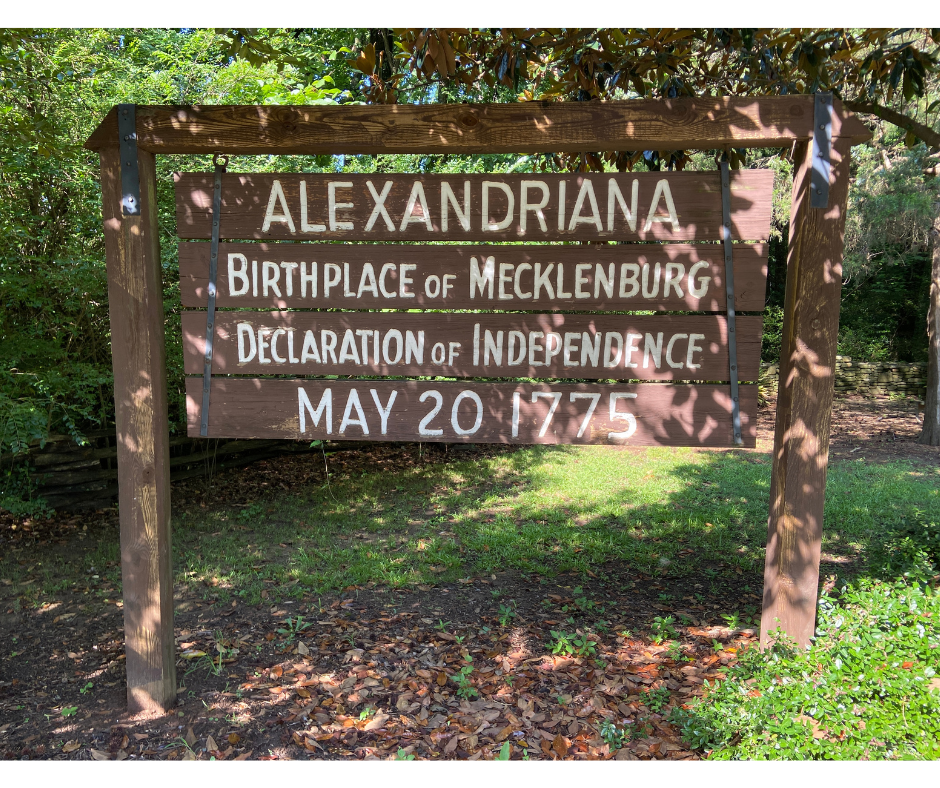

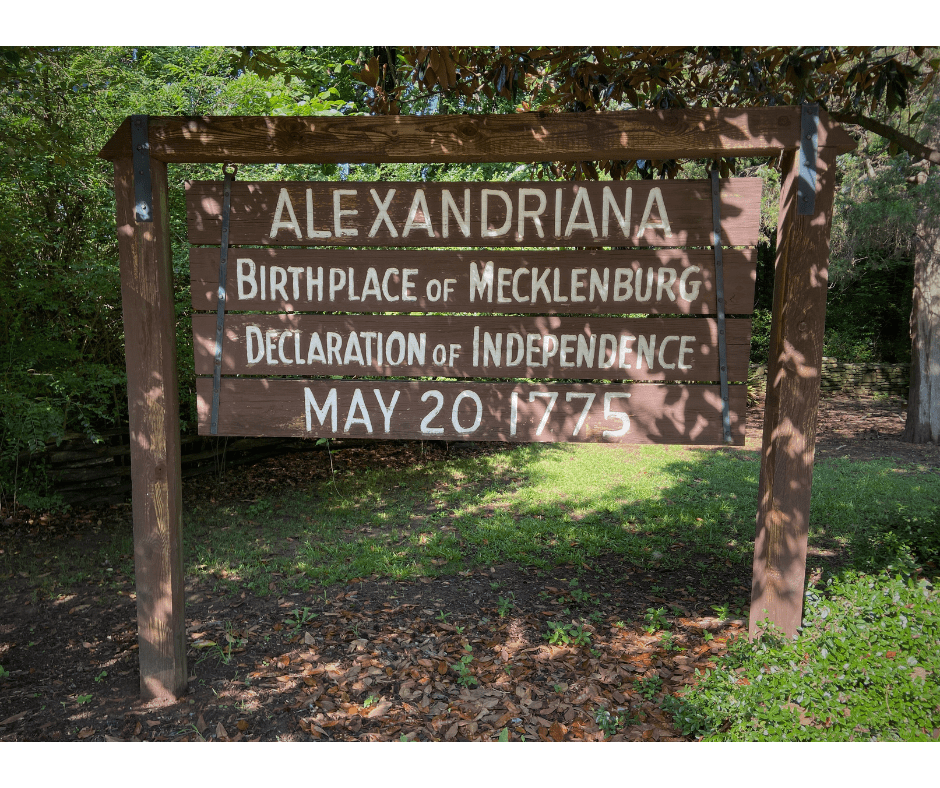

John McKnitt Alexander, whose plantation “Alexandriana” became a focal point for revolutionary organizing, exemplified this synthesis of frontier practicality and learned discourse. As depicted in LeGette Blythe’s historical novel Alexandriana, the Alexander home served as more than a prosperous plantation; it functioned as an intellectual hub where ideas about liberty, self-governance, and resistance to tyranny were debated alongside practical strategies for colonial defense. The Princeton-educated ministers and landowners of Mecklenburg could justify their rebellion not merely as frontier defiance but as a principled stand grounded in political philosophy and moral conviction.

From Tension to Declaration: The May 1775 Moment

By the spring of 1775, Mecklenburg County had become a powder keg of revolutionary sentiment. When news of the battles at Lexington and Concord reached Charlotte in May, it provided the spark needed to ignite open rebellion. According to historical accounts – though disputed by some scholars – Colonel Thomas Polk summoned militia representatives to the Charlotte courthouse on May 19, 1775. The gathering elected Abraham Alexander as chairman and John McKnitt Alexander as secretary, then drafted what would become known as the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence.

The language of this declaration was uncompromising. The assembled representatives allegedly resolved that they would “dissolve the political bands which have connected us to the Mother Country” and proclaimed themselves “free and independent” from British rule – fourteen months before the Continental Congress would adopt similar language in Philadelphia. Whether this specific document existed in the form tradition claims remains debated among historians. However, the indisputable historical record shows that Mecklenburg County did produce the Mecklenburg Resolves on May 31, 1775, which called for local self-governance and rejected Crown authority in practical terms.

David Fleming’s investigation in Who’s Your Founding Father? argues compellingly that the distinction between these two documents may be less significant than commonly assumed. Both reflected the same revolutionary spirit, and the later destruction of county records in an 1800 fire created ambiguity that historians have exploited. What matters historically is not whether a specific piece of parchment survived, but that Mecklenburg County’s residents genuinely believed they had declared independence first – and that this belief shaped their identity and actions throughout the Revolutionary War.

The Broader Carolina Context

Mecklenburg County’s revolutionary fervor did not emerge in isolation but reflected broader patterns across North Carolina’s backcountry. The colony had long been divided between the coastal elite, who maintained closer ties to British authority and benefited from established trade networks, and the interior settlers, who felt neglected and exploited by both colonial and imperial governance. The Regulator movement of 1768-1771, though ultimately suppressed, demonstrated the depth of backcountry resentment against corrupt officials and unequal taxation.

Taylor’s American Colonies emphasizes how North Carolina’s geography created distinctive political tensions. The lack of good harbors and the challenge of navigating the Outer Banks limited direct trade with Britain, forcing backcountry farmers to market their goods through Virginia or South Carolina. This geographic isolation contributed to a sense of independence but also economic frustration. When revolutionary resistance began focusing on non-importation and self-sufficiency, North Carolina’s backcountry settlers found themselves ideally positioned – both practically and psychologically – to embrace economic separation from Britain.

The Role of Local Leadership

The patriot mindset in Mecklenburg County was not merely spontaneous popular uprising but reflected deliberate cultivation by local leaders. Figures like Thomas Polk, the Alexander family members, and Presbyterian ministers created networks of communication and mutual support that could rapidly mobilize community response to British actions. These leaders hosted meetings, circulated pamphlets and newspapers, and ensured that news from other colonies reached even remote settlements.

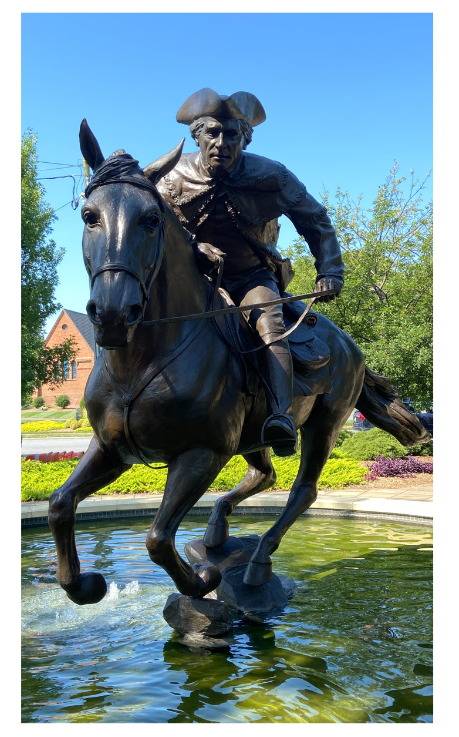

Captain James Jack’s legendary ride to Philadelphia, carrying news of Mecklenburg’s declarations to the Continental Congress, exemplifies this organized activism. While often compared to Paul Revere’s more famous midnight ride, Jack’s journey covered more than 500 miles through difficult terrain. The fact that the community could quickly select a messenger and coordinate such a mission demonstrates the level of political sophistication and preparation that existed in this supposedly frontier region. These were not impulsive rebels but organized revolutionaries who understood the importance of coordination and communication.

Legacy and Memory

The question of whether Mecklenburg County truly declared independence first, or whether the story represents wishful thinking and reconstructed memory, has occupied historians for two centuries. Five U.S. presidents – Taft, Wilson, Eisenhower, Ford, and George H.W. Bush – traveled to Charlotte to honor the claim, and North Carolina’s state flag and license plates proudly display “May 20, 1775” as the date of its first declaration of independence. This persistent commemoration reveals something important regardless of strict historical accuracy: the people of Mecklenburg County believed they acted first, and this belief shaped their understanding of their role in American independence.

In The First America Declaration of Independence?, Scott Syfert argues persuasively that the controversy over authenticity has obscured the more significant historical reality: Mecklenburg County residents did take radical steps toward independence remarkably early in the revolutionary process. Whether the exact language of the May 20 declaration is precisely as remembered matters less than the documented fact that this region rejected British authority in concrete, organized ways before most other American communities. The Mecklenburg Resolves of May 31, 1775, which survive in multiple contemporary accounts, established local governance independent of Crown authority and explicitly rejected parliamentary control.

A Distinctly Southern Revolution

The development of the patriot mindset in Mecklenburg County represents a distinctly Southern contribution to American revolutionary thought. Unlike New England, where merchant interests and urban intellectuals often led resistance, or the Chesapeake, where plantation aristocrats debated rights and representation, North Carolina’s backcountry revolution emerged from Scots-Irish settlers, Presbyterian theology, frontier pragmatism, and accumulated grievances against both colonial and imperial authority.

This revolutionary spirit drew from deep wells of cultural memory, religious conviction, intellectual sophistication, and practical necessity. The Scots-Irish brought resistance in their bones, forged through generations of discrimination. Presbyterian theology provided moral justification for questioning unjust authority. Princeton-educated leaders offered philosophical frameworks for understanding natural rights and legitimate government. And the practical experience of frontier life created communities accustomed to self-reliance and collective decision-making.

When these elements converged in May 1775, Mecklenburg County was prepared to do what seemed radical elsewhere: declare independence not tentatively or hypothetically, but as a concrete political reality. Whether historians ultimately validate every detail of the traditional account matters less than recognizing the genuine revolutionary fervor that existed in this remote corner of North Carolina. The patriot mindset did not begin in Philadelphia or Boston alone; it was simultaneously igniting in places like Charlotte, where different histories and distinct grievances produced the same conclusion: that free people must govern themselves or cease to be free.

The story of Mecklenburg County’s revolutionary development challenges us to recognize the multiple origins and diverse sources of American independence. The Revolution was not one movement but many, not one declaration but several, not one founding moment but an extended process of communities across thirteen colonies reaching similar conclusions through different paths.

In understanding how the patriot mindset developed in North Carolina’s backcountry, we gain a richer, more complete picture of how America became independent – not through singular genius in a single place, but through the converging determination of many communities, each with its own story of resistance, its own declaration of freedom, and its own claim to have helped light freedom’s first flame.

A Note On This Series

This journey through Revolutionary history is as much about the evolution of historical understanding as the Revolution itself. History isn’t static – each generation reinterprets the past through its own concerns, asking different questions and prioritizing different sources. By reading these books in dialogue across 250 years, we’ll witness how scholarship evolves, how narratives get challenged, and how forgotten stories resurface.

This isn’t about declaring one interpretation “right” and another “wrong,” but appreciating the richness that emerges when multiple perspectives illuminate the same transformative moment. These books won’t provide definitive answers – history rarely does – but they equip us to think more clearly about how real people facing genuine uncertainty chose independence, how ideas had consequences, and how the work of creating a more perfect union continues. As we mark this anniversary, we honor the Revolutionary generation by reading deeply, thinking critically, and engaging seriously with both the brilliance and blind spots of what they created.