My family knows the game I play when we go to our favorite local restaurant, 131 Main. They shake their heads, but they usually play along. Unsuspecting guests are unwittingly invited into the game as well, usually to my wife’s chagrin. It’s simple but profound, and always sparks a lively conversation.

The game starts with a simple question: Usually about half way through our meal, I will ask, “How many servers, hosts, etc. have stopped by our table and engaged us?“

Their answer is almost always wrong (on the low side); my personal record is 7.

Which brings us to today’s topic, the third in a series of four exploring how food experiences reveal fundamental truths about social interaction, identity, and community through the lens of Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical sociology. Read the series here; continue with Part Three below.

The server refilled your beverage glass before you noticed it was empty. She remembered your shellfish allergy from the reservation notes. When your date’s entrée arrived overcooked, another server whisked it away with genuine apology, returning minutes later with a perfect replacement – and a complimentary dessert. The meal felt effortless, warm, authentic. And it was completely choreographed.

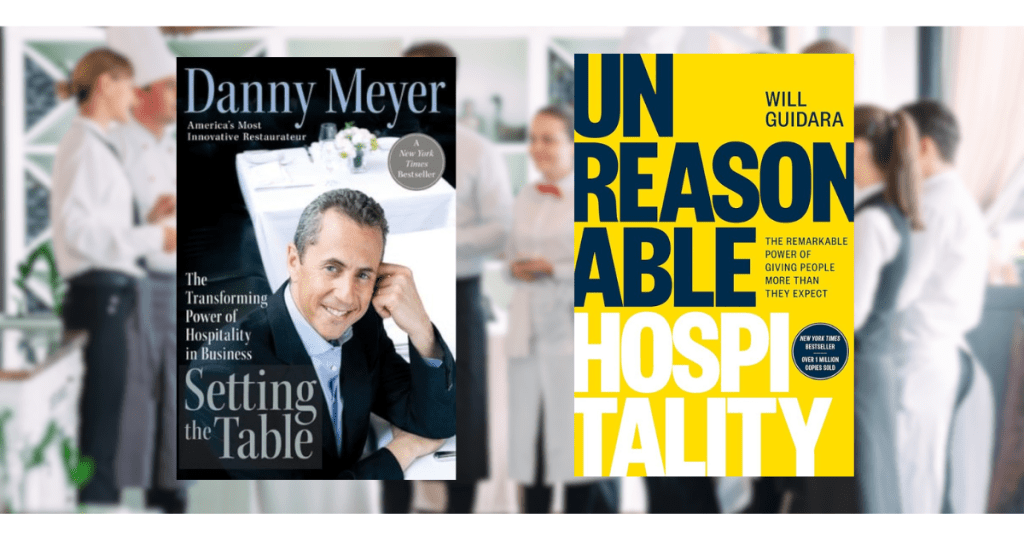

Danny Meyer built a restaurant empire on a paradox: the best hospitality feels spontaneous but requires meticulous planning. In Setting the Table, Meyer describes what he calls “enlightened hospitality” – a philosophy that transformed the service industry. At its core lies a tension sociologist Erving Goffman would recognize immediately: How do you engineer authentic human connection? How do you perform genuine care?

Will Guidara, Meyer’s protégé who led Eleven Madison Park to the top of the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list, pushed this paradox further. In Unreasonable Hospitality, Guidara describes deliberately breaking the script to create unrehearsed magic. His team once overheard guests mention they’d never had a New York hot dog, so they sent a runner to the street cart and served it on fine china as an additional course. For a family from Spain, they transformed a private dining room into a miniature beach, complete with sand. These gestures weren’t in any manual. They were improvised performances of care that cost money while generating nothing but goodwill – and legend.

Together, Meyer and Guidara represent two poles of the same challenge: How do you systematize spontaneity? How do you make the rehearsed feel unrehearsed?

Service vs. Hospitality: Technique vs. Performance

Meyer distinguishes sharply between service and hospitality. Service is technical – delivering food and drink correctly. Anyone can learn it. Hospitality is emotional – making guests feel cared for. It requires what Meyer calls “emotional intelligence, empathy, and thoughtfulness.” But here’s the contradiction: Meyer systematizes these supposedly spontaneous qualities. He hires for them, trains for them, rewards them. He’s created theater where servers must improvise within carefully constructed parameters, where authentic emotion is both the goal and the product.

Guidara inherited a restaurant that delivered flawless service – technically perfect, precisely timed, utterly professional. But it felt cold. Guests were impressed but not moved. The performance was too polished, too obviously rehearsed. What was missing was the human moment – the break in the script that reminds diners they’re being served by people, not automatons.

This is Goffman’s dramaturgical theory as commercial practice. These restaurants are elaborate stages with clearly defined regions. The dining room is “front stage,” where servers perform gracious hospitality. The kitchen is “backstage,” where the performance is prepared – not just the food, but the emotional labor required to seem effortlessly caring for hours.

PERSONAL OBSERVATION: In all our years of going to 131 Main, we’ve never had a “bad” experience – and only one has been less than stellar. The floor manager walked by, noticed that only one entree had been delivered to our table of four, and beyond earshot but in range of my inquisitive eye, talked to our primary server. She came by apologize for the miscue, took my entree to be boxed up, and in just a few minutes all four entrees were delivered by a pair of servers. The manager apologized and removed the entree from our bill.

Was this technique or performance?

Reading the Room: The Art of Improvisation

Great hospitality requires constant calibration. Servers must read each table: Are these guests celebrating or conducting business? Do they want conversation or privacy? Are they in a hurry or lingering? This is impression management in real time, adjusting the performance to match unstated needs. A skilled server shifts registers instantly: warm with one table, briskly efficient with another, invisible to a couple deep in conversation.

Meyer hires for what he calls “hospitality quotient” – an intuitive understanding of how to make others comfortable. But even innate empathy needs refinement through training. His restaurants teach servers “dramaturgical discipline” (Goffman’s term): maintaining character under pressure, never letting the mask slip, preserving the illusion that this care is spontaneous.

Guidara pushes beyond discipline into creativity. He instituted “dreamweaver” roles – staff whose sole job was finding opportunities for unreasonable gestures. They’d listen tactfully to conversations, looking for moments to surprise and delight. Overheard a birthday? Not just a candle on dessert, but perhaps the sommelier opens something special from the birth year. Mentioned you’re from Chicago? Maybe a house-made deep-dish pizza appears, completely off-menu.

These gestures required different training. Staff needed permission to break the script, but also judgment to know when breaking it enhanced rather than disrupted the experience. They had to perform confidence, creativity, and care – while maintaining the structure that allowed a complex restaurant to function.

The pre-shift meeting became crucial in both operations. Here, teams review reservations, discuss VIPs, share information about guests’ preferences or occasions. They’re literally preparing for performance: who’s in the audience tonight, what they might need, how to deliver it. It’s backstage rehearsal for the front stage show.

Blurring the Boundaries: When Backstage Becomes Front Stage

The kitchen is traditionally the ultimate backstage – hot, chaotic, often profane. Here, cooks can drop the serenity performance and reveal the stress and intense coordination required for seamless dining. The swinging door is a literal threshold between raw reality and polished performance.

But Meyer and Guidara complicate this binary. Meyer prefers open kitchens, deliberately blurring front and backstage. If diners can see the kitchen, it becomes part of the performance – chefs must maintain some front stage behavior even in their traditional backstage space. The performance expands to encompass more truth.

Guidara went further, involving the entire team in hospitality, not just servers. Dishwashers, prep cooks, even accountants contributed ideas for guest experiences. The backstage crew became part of the front stage performance, invested in emotional experience, not just technical execution. This distributed emotional labor across the organization but raised the stakes – everyone needed some dramaturgical discipline.

The Paradox of Performing Authenticity

Meyer insists that true hospitality requires servers to bring their authentic selves to work. He wants people, not automatons following scripts. This creates fascinating tension: servers must be genuine, but their genuineness must serve commercial interests. They must care, but not too much. They must be friendly, but maintain professional boundaries. They’re asked to perform authenticity itself.

Guidara frames this as “prestige without pretense” – delivering world-class experiences without stuffiness. His staff performed simultaneously as highly trained professionals and warm, genuine people who happened to serve food. They needed to know which fork goes where while also laughing at themselves, acknowledging mistakes with grace, treating a street hot dog with the same respect as a truffle course.

This is emotional labor at its most sophisticated. Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild coined the term to describe work requiring managing one’s feelings to create observable displays. Flight attendants perform serenity during turbulence. Bill collectors perform stern authority. Restaurant servers perform genuine warmth toward strangers – again and again, table after table, shift after shift.

The risk, Hochschild warned, is alienation – when performing emotion becomes so divorced from feeling it that workers lose touch with authentic selves. Meyer and Guidara both recognize this danger. Meyer emphasizes employee well-being, competitive pay, and advancement, understanding you cannot extract authentic-seeming hospitality from miserable workers. Guidara instituted family meals, team outings, and celebration culture, ensuring the care his staff performed outward was mirrored by care they received internally.

The investment serves strategic purposes. Happy employees provide better hospitality, creating better experiences, generating more revenue and prestige. The care flows both directions, but it’s still choreography.

The Economics of Breaking the Script

Guidara’s “unreasonable” gestures raise questions about the economics of performance. Sending runners for street hot dogs, building beaches in dining rooms, opening rare wines at a loss – these seem to contradict profit maximization. But they generate something more valuable than immediate revenue: stories. Guests don’t just remember the meal; they remember the magic. They become evangelists, telling everyone about the restaurant that somehow knew exactly what would delight them.

This is impression management on a grand scale. The unreasonable gesture performs several things simultaneously: the restaurant values experience over efficiency, sees guests as individuals rather than covers, has resources to spare for pure generosity. These performances build brand value far exceeding immediate cost.

But there’s risk. Once unreasonable becomes expected, it loses power. If every guest anticipates a surprise, the surprise ceases to surprise. Guidara’s team had to constantly escalate, finding new ways to break the script, new performances of spontaneous care. The unreasonable had to remain genuinely unreasonable, which meant it couldn’t be completely systematized. They needed structure loose enough to allow real improvisation.

This is the central paradox of both philosophies: you must build systems that enable breaking the system. You must rehearse spontaneity. You must perform authenticity so skillfully that it becomes indistinguishable from the real thing.

Team Performance and Collective Care

Goffman wrote about “teams” – groups of performers cooperating to maintain a particular definition of the situation. Restaurants operate as complex team performances. Servers, runners, bartenders, hosts, and kitchen staff all collaborate to sustain the illusion of effortless hospitality. When one team member breaks character – a visibly stressed server, a curt host, a runner slamming down plates – the entire performance suffers.

Meyer’s training emphasizes “dramaturgical loyalty”: team members must support each other’s performances, cover mistakes, and maintain unified front stage behavior regardless of backstage chaos. If a server forgets to fire a course, the team rallies to correct it invisibly. If a guest complaint threatens the performance, everyone adjusts to restore equilibrium.

Guidara extended the team concept to include guests. He recognized diners also perform – they’re performing sophistication to appreciate haute cuisine, performing celebration or romance, performing social identities. The restaurant’s job was supporting these guest performances, being the stage where their special occasions could unfold successfully.

This meant sometimes letting guests lead, even when it meant bending the restaurant’s script. If a table wanted to linger over dessert for two hours, closing the kitchen around them, that became part of the performance. If guests wanted photos when most fine dining establishments discouraged it, Guidara’s team offered to take the photos, turning a potential protocol breach into enhanced experience.

The restaurant table is a stage where multiple performances intersect. Servers perform hospitality. Guests perform being worthy of such hospitality – appreciative, knowledgeable, appropriately demanding. The restaurant itself performs identity: casual or formal, traditional or innovative, exclusive or accessible. All these performances must align for the experience to succeed.

Digital Stages and Expanded Audiences

The digital age complicates these performances. Online reviews mean every guest is a potential critic, every meal a potential public performance. Servers must manage not just immediate impressions but photographable moments. Food must be Instagram-worthy; the experience must generate positive Yelp reviews. The performance extends beyond physical space into digital realm, evaluated by strangers and compared against countless competing performances.

Guidara understood this intuitively. The unreasonable gestures weren’t just about recipients – they were about the stories recipients would tell. Each surprise was designed to be shareable, to become legend. When Eleven Madison Park climbed the World’s 50 Best list, it wasn’t just technical excellence. It was accumulated stories of magic, circulating through social networks, building a reputation for hospitality transcending mere service.

But this created new pressures. Staff had to perform for two audiences simultaneously: guests in the room and potential thousands who might see photos or read reviews. A beautifully plated dish had to photograph well. An unreasonable gesture had to be story-worthy. The performance became more complex, more layered, more exhausting.

Meyer and Guidara navigated this by focusing on the immediate audience – the actual humans in their dining rooms. Yes, digital performance mattered, but it had to emerge organically from genuine hospitality rather than being engineered for likes and shares. The performance of care had to convince in person before it could convince online.

When Performance Dissolves Into Identity

The profound question at the heart of both Setting the Table and Unreasonable Hospitality is whether performing care can become real care. Meyer believes it can – that consistently acting with genuine hospitality makes it who you are rather than what you’re performing. Guidara pushes further, arguing unreasonable hospitality isn’t performance at all, but a mindset, a way of moving through the world that sees every interaction as an opportunity for generosity.

Goffman might have been more skeptical, seeing the self as nothing more than the sum of its performances. Perhaps the truth lies between: we perform hospitality until we internalize the script, and then the line between authentic and performed dissolves entirely. The server who’s practiced warmth for a decade may no longer distinguish between genuine feeling and professional performance – and perhaps that distinction no longer matters.

Consider the implications. If we perform care long enough, with enough consistency and skill, does it matter whether we “really” feel it? If the guest experiences genuine warmth, if they leave feeling valued and seen, does the server’s inner emotional state change the moral or practical reality of what happened?

This challenges our usual assumptions about authenticity. We tend to think authentic means unperformed, spontaneous, arising naturally from inner feeling. But Meyer and Guidara suggest another possibility: that authentic means fully committed to the performance, bringing your whole self to the work of caring for others, even – or especially – when it’s difficult.

The Theater of Everyday Generosity

In an economy increasingly built on service and experience rather than goods, we’re all in the hospitality business now. We all manage impressions, perform emotional labor, and navigate the tension between authenticity and strategic self-presentation. Customer service representatives, teachers, healthcare workers, flight attendants – all perform care as part of their professional roles.

Meyer’s restaurants and Guidara’s unreasonable gestures are simply more honest about the choreography, more intentional about the performance. They’ve turned the art of seeming real into a refined craft. But they’ve also revealed something hopeful: that performed care, executed with enough skill and genuine investment, can create real connection.

The script, when well-written and expertly delivered, can facilitate authentic human moments. There’s dignity in the performance, in choosing to show up night after night and make strangers feel valued, seen, cared for. The emotional labor is real labor, worthy of respect and compensation. And the moments of connection it creates, however fleeting, are genuinely valuable.

The restaurant is a microcosm of social life itself – a stage where we practice being generous, attentive, and present. Where we learn that authenticity and performance aren’t opposites but dance partners, each making the other possible. Where we discover that the most genuine moments often emerge from carefully constructed circumstances.

Think about the last time you felt truly welcomed somewhere – a hotel, a store, a friend’s home. Chances are, some of that welcome was performed. Your friend cleaned the house, planned the meal, performed the role of gracious host. The hotel desk clerk followed training on how to greet guests warmly. The store employee was taught to make eye contact and smile. Does knowing this diminish the experience? Or does it reveal how much effort people invest in making others feel good?

Meyer and Guidara have built careers on a beautiful paradox: you can engineer magic, choreograph spontaneity, and perform your way into authentic human connection. Their restaurants prove Goffman was right about social life being theatrical – but also that theater, at its best, reveals deeper truths.

The performance of hospitality, sustained with enough care and creativity, becomes indistinguishable from hospitality itself. And in that dissolution of boundaries between real and performed, we find something worth celebrating: the possibility that all our social performances, executed with genuine care, might actually make us better, kinder, more attentive to each other’s humanity.

The Lesson From the Kitchen Door

The real lesson from the front and backstage of great restaurants isn’t that hospitality is fake. It’s that performing care, again and again, with discipline and creativity and unreasonable generosity, is one of the most authentic things we can do.

When the server remembers your shellfish allergy, when the team builds a beach in a dining room for homesick guests, when the kitchen stays open late because you’re clearly celebrating something important – these are performances, yes. But they’re performances in service of something real: the fundamental human need to be seen, valued, and cared for.

Goffman taught us that all social interaction involves performance. We’re always managing impressions, always aware of our audience, always making choices about how to present ourselves. The question isn’t whether to perform – we can’t not perform. The question is what kind of performance to give, what values to embody, what kind of world to create through our repeated small dramas of daily life.

Meyer and Guidara chose to perform generosity, warmth, and attention. They built systems to support these performances and trained teams to execute them. They invested enormous resources in making strangers feel special for a few hours. And in doing so, they demonstrated that the performance of care, when taken seriously as craft and commitment, creates something genuine.

The swinging kitchen door separates front stage from backstage, performance from preparation, the polished from the raw. But in the best restaurants – and perhaps in the best lives – that door swings freely. The backstage work of preparation makes the front stage magic possible. The front stage performance gives meaning to the backstage effort. They’re not opposites but partners in creating experiences worth remembering.

We’re all standing on one side of that door or the other, all the time. Sometimes we’re performing for others; sometimes we’re preparing our performances; sometimes we’re the audience for someone else’s carefully crafted care. Understanding this doesn’t diminish the magic. It deepens our appreciation for the work involved in making each other feel human, valued, and connected in a world that too often treats us as interchangeable.

That’s the gift Meyer and Guidara offer: not just better restaurants, but a clearer understanding of what we’re all doing when we choose to care for each other, even when – especially when – it requires effort, training, and conscious performance. The care is real. The performance makes it possible. And that’s not a contradiction. That’s just life, lived with intention and grace.

Part of a regular series on 27gen, entitled Wednesday Weekly Reader.

During my elementary school years one of the things I looked forward to the most was the delivery of “My Weekly Reader,” a weekly educational magazine designed for children and containing news-based current events.

It became a regular part of my love for reading, and helped develop my curiosity about the world around us.