January and February – Seeds of Rebellion, Part Seven

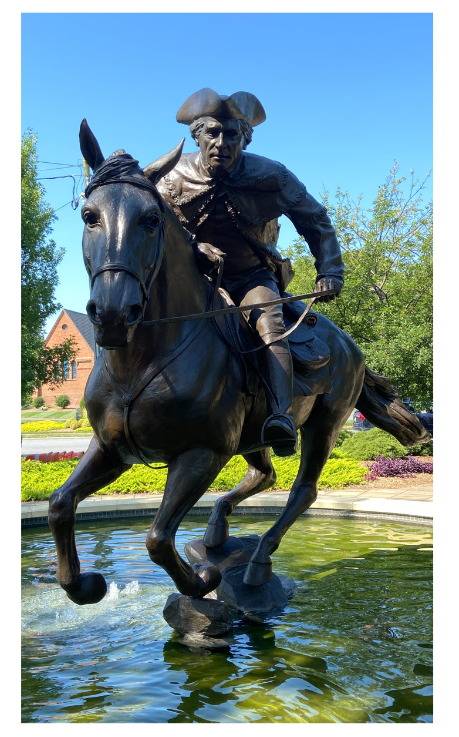

On a frozen night in December 1776, the Continental Army was dissolving. Enlistments were expiring. Men were walking home barefoot through snow, leaving bloody tracks on Pennsylvania roads. Thomas Paine, huddled by a campfire, scratched out the words that would become immortal: These are the times that try men’s souls. Washington had them read aloud to the troops before crossing the Delaware.

That moment – desperate, improbable, morally electric – sits at the heart of what Robert Middlekauff accomplishes in The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. The book asks a question we think we know the answer to but actually don’t: Why did these men keep fighting? And more uncomfortably – what were they actually fighting for?

In an era when the word “revolution” gets applied to everything from phone apps to fitness routines, reading Middlekauff is a corrective act. Real revolution, he shows us, is anguish dressed up in the rhetoric of glory.

The Scholar Behind the Story

Robert Middlekauff published The Glorious Cause in 1982 as the first volume in the Oxford History of the United States series – a scholarly enterprise that set out to give Americans a definitive, peer-reviewed account of their own history. Middlekauff spent his career at the University of California, Berkeley, and brought to the project the patient, rigorous sensibility of an intellectual historian who had previously written about Puritan education and the Mather dynasty.

That background matters enormously. Middlekauff is fundamentally interested in how people think – how ideas shape behavior, how belief systems crack under pressure, how ideology becomes action. He is not a military historian cataloguing troop movements, nor is he a social historian recovering forgotten voices from the margins. He is a historian of the colonial mind, and that makes The Glorious Cause a different kind of war book than most readers expect.

He wrote it at a curious cultural moment: the revolutionary bicentennial had just passed, Ronald Reagan had just been elected on a platform drenched in patriotic nostalgia, and the academy was beginning to fragment into competing methodological camps. Middlekauff’s book was, in part, a serious scholar’s attempt to reclaim the Revolution from both the sentimentalists and the cynics.

The Central Argument: Ideology Made Flesh

Middlekauff’s core interpretation is deceptively simple: the American Revolution was ideologically sincere. This was not a tax revolt dressed up in philosophical language. The colonial leaders – and eventually ordinary farmers and tradesmen – genuinely believed that British policy after 1763 represented a coordinated assault on English liberties that they, as Englishmen, were duty-bound to resist.

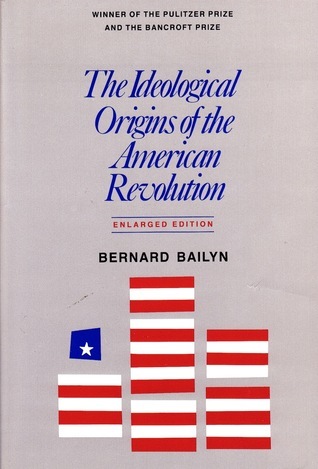

This puts him in direct conversation with the “republican synthesis” school of historians like Bernard Bailyn, whose Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967) argued that colonists operated within a coherent, if somewhat paranoid, Whig political tradition. Middlekauff accepts and extends this framework, but where Bailyn stops at ideas, Middlekauff follows them into the mud of Valley Forge.

The book traces how that ideology was tested – and how testing it transformed it. By 1776, resistance to Parliamentary taxation had become something larger: a conviction that Providence itself had assigned Americans a role in the drama of human freedom. This was not cynical rhetoric. Middlekauff argues it was felt, with all the force of religious experience, by men who lived in a culture where political and theological categories were still deeply intertwined.

He writes of the soldiers who stayed: “What kept them going was not pay, not bounties, not discipline, but a sense that they were engaged in something larger than themselves – a cause, glorious in their own word for it, that demanded everything they had.” The word “glorious” in the title is their word, not his. He’s holding them accountable to it.

The Voice on the Page

Middlekauff writes with authority and occasional grace. He is not a stylist in the manner of David McCullough, but he has a gift for compression – for capturing the texture of an experience in a sentence or two before moving the argument forward.

On the Continental soldier’s psychology, he is particularly sharp. He describes men who feared disgrace more than death, who were “motivated by shame as much as glory,” carrying into battle the weight of community expectation and the crushing awareness that their neighbors would know if they ran. This is not the heroic framing of popular history. It is something truer and more interesting: men doing brave things for complicated, deeply human reasons.

His account of the political crisis is equally precise. Of the colonial assemblies’ escalating confrontations with Parliament, he observes that each British attempt to reassert authority convinced colonists not of their own rebelliousness but of Britain’s corruption – confirming every fear the Whig tradition had taught them to hold. The machinery of radicalization, Middlekauff shows, ran on genuine grievance processed through a specific ideological lens.

Dialogue with the Series

Those who have followed Booked for the Revolution will recognize both the continuities and the tensions with earlier readings.

Middlekauff shares Bailyn’s respect for the power of ideas, but where Bailyn’s Ideological Origins is a book of pamphlets and arguments, The Glorious Cause is a book of consequences – what happened when those ideas collided with British regulars, smallpox, and supply shortages. It is Bailyn made incarnate.

Alan Taylor’s American Colonies (2001) offers the most striking contrast in scope. Where Middlekauff zooms in on the Revolutionary generation and the specific ideological world it inhabited, Taylor pulls back to the widest possible lens – a hemispheric, multi-century story in which British North America is just one contested zone among many, populated by overlapping and colliding empires, Indigenous nations, and enslaved Africans. Taylor’s colonists are not proto-Americans yearning for liberty; they are settlers in an unstable, violent Atlantic world shaped by forces far larger than any pamphlet debate. Reading the two books back to back is instructive: Middlekauff’s Revolution feels inevitable and coherent; Taylor’s makes it look contingent and strange. Both effects are useful. Taylor reminds us what Middlekauff’s ideological framework cannot see – all those lives and peoples for whom the Whig tradition was simply irrelevant.

T.H. Breen’s American Insurgents, American Patriots (2010) is a more direct interlocutor, and in some ways the more revealing one. Breen agrees with Middlekauff that ordinary Americans were genuinely motivated – but he relocates that motivation from the elite discourse of constitutional rights to the experience of local community enforcement. For Breen, the Revolution was driven from below, by farmers and tradesmen who organized committees of safety, policed Loyalist neighbors, and built a coercive popular movement before the Continental Congress had fully committed to independence. Middlekauff’s soldiers are moved by ideology absorbed from their political leaders. Breen’s insurgents are moved by rage, solidarity, and the intoxicating power of collective action. Both accounts ring true. Together, they suggest that the Revolution was simultaneously a principled argument conducted at the top and a fierce, sometimes violent social movement conducted at the bottom – and that these two things fed each other in ways neither Middlekauff nor Breen fully capture alone.

What We’ve Learned Since 1982

Four decades of scholarship have complicated Middlekauff’s picture considerably. The Revolution he describes is, in the phrase historians now use, “the Revolution from above” – the Revolution of founders and Continental officers and colonial assemblies.

We now understand far more about Loyalism than Middlekauff could draw on in 1982 – the deep communities of colonists who saw rebellion not as liberty but as mob rule, and who paid for that view with exile and dispossession. We understand more about how Indigenous nations navigated the conflict as a genuine geopolitical contest with their own interests at stake. We understand more about enslaved people who fled to British lines because freedom, for them, came wearing a red coat.

None of this invalidates Middlekauff’s achievement. It contextualizes it. The Glorious Cause tells us what the Revolution looked like to the people who gave it its name and carried it to completion. That perspective is historically essential, even when – especially when – it is incomplete.

The book also predates the full flowering of Atlantic history, which situates the American Revolution within a broader hemispheric context of imperial crisis, Caribbean sugar economies, and European great-power rivalry. Middlekauff’s Revolution is largely a North American story. That was the convention of his time; it is a limitation of ours.

Why Read This in 2026?

Because we are living through another moment when the word “revolution” is cheap and the thing itself – costly, ambiguous, morally unresolved – is poorly understood.

The Glorious Cause restores the cost. It shows that the founders were not superhuman visionaries but frightened, improvising men who had talked themselves into a corner and then discovered, to their own amazement, that they believed what they’d said. It shows that ideology is not mere decoration on the surface of interests – it gets inside people and makes them do things that interests alone would never justify.

It also shows the gap between the cause’s stated ideals and its actual beneficiaries – a gap that 250 years of American history has been spent, imperfectly and incompletely, trying to close. In a year when that project feels newly contested, understanding where the gap came from matters.

Read Middlekauff for what he does brilliantly: the intellectual and military architecture of independence, rendered with scholarly honesty and real narrative drive. Read him alongside Taylor and Breen and Bailyn for the fuller picture. Together, they don’t give you mythology or cynicism. They give you something better – history.

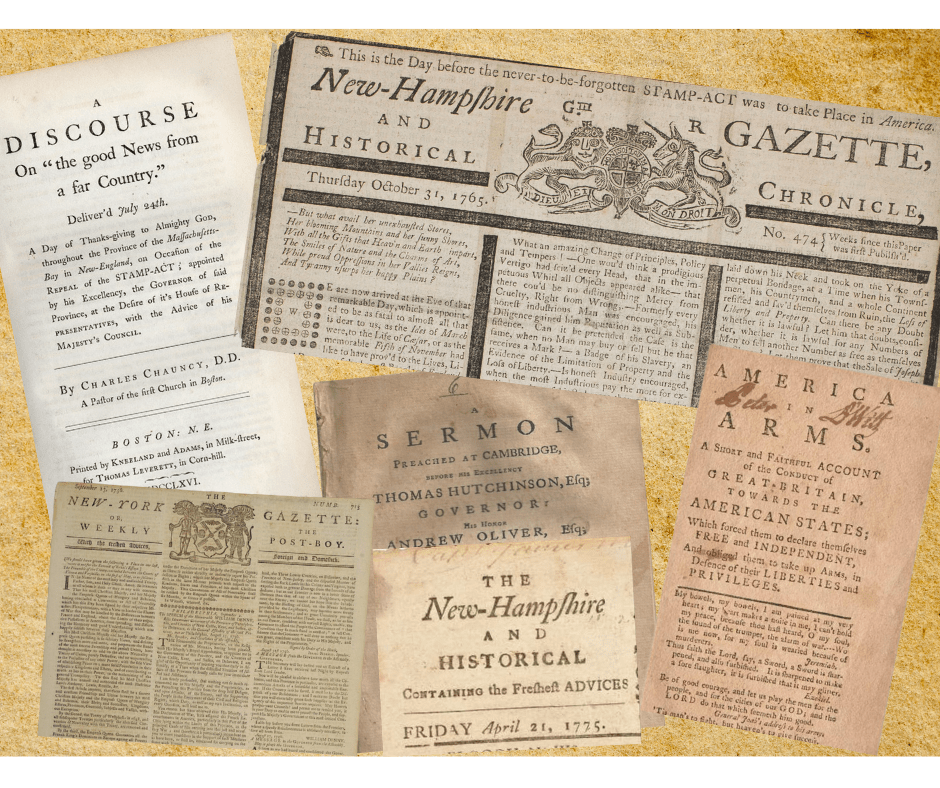

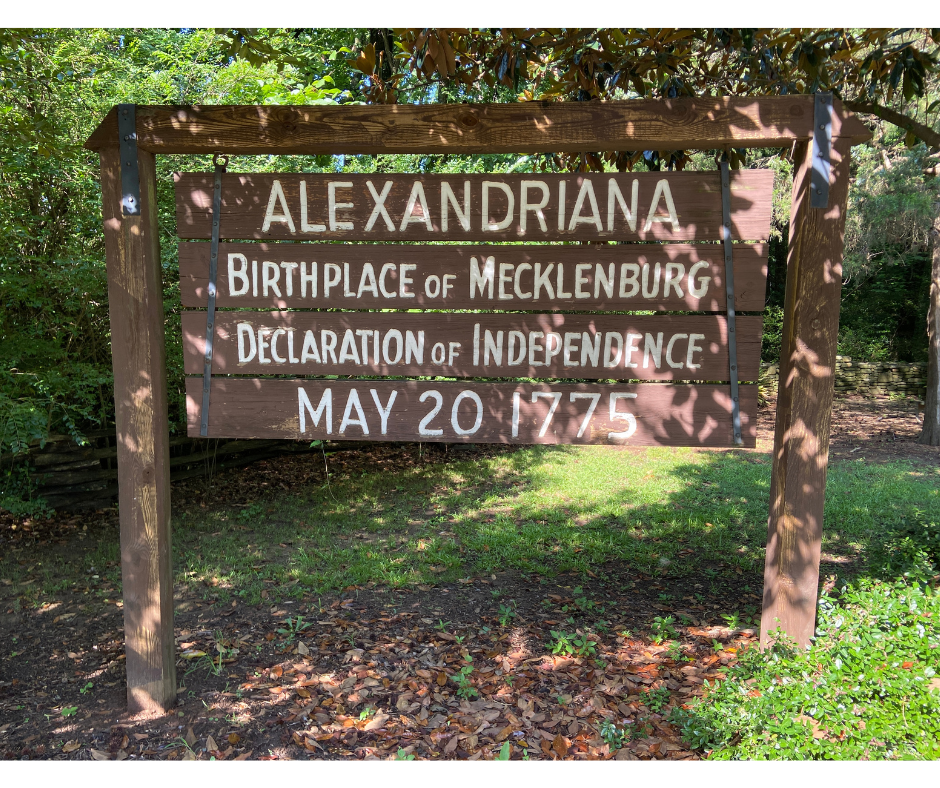

Looking Ahead – The Gathering Storm: The next two months of articles will cover the most compressed, intense period of the pre-Revolutionary crisis – the twenty-four months (1774-1775) when resistance became rebellion and rebellion crystallized into a formal declaration of independence. This is when abstract grievances turned into armed conflict, when loyalties were tested and fractured, when the unthinkable became inevitable. “The Gathering Storm” metaphor captures both the mounting tension and the sense that forces beyond any individual’s control were converging toward a breaking point.

A Note on This Series

This journey through Revolutionary history is as much about the evolution of historical understanding as the Revolution itself. History isn’t static – each generation reinterprets the past through its own concerns, asking different questions and prioritizing different sources. By reading these books in dialogue across 250 years, we’ll witness how scholarship evolves, how narratives get challenged, and how forgotten stories resurface.

This isn’t about declaring one interpretation “right” and another “wrong,” but appreciating the richness that emerges when multiple perspectives illuminate the same transformative moment. These books won’t provide definitive answers – history rarely does – but they equip us to think more clearly about how real people facing genuine uncertainty chose independence, how ideas had consequences, and how the work of creating a more perfect union continues. As we mark this anniversary, we honor the Revolutionary generation by reading deeply, thinking critically, and engaging seriously with both the brilliance and blind spots of what they created.