March and April – The Gathering Storm, Part One

Imagine you are a prosperous Virginia planter in the spring of 1774. You drink tea every morning, you swear allegiance to King George III, and you find the hotheads up in Boston as alarming as the Parliament they are defying. War is unthinkable. Independence is treasonous. And yet, within twelve months, you will be drilling with a militia, signing non-importation agreements, and telling yourself – with more conviction than you actually feel – that armed resistance was always the only honorable path.

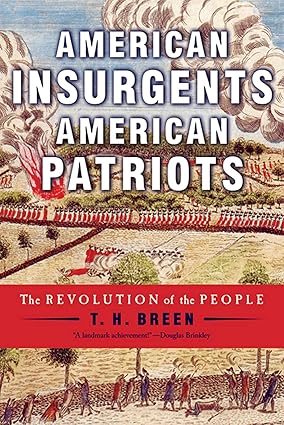

That psychological journey, taken by hundreds of thousands of colonists who never wanted a revolution, is the subject of Mary Beth Norton’s distinguished 1774: The Long Year of Revolution (Knopf, 2020). In an era when Americans are once again arguing furiously about the meaning of their founding, about who belongs in the national story, and about how a democracy fractures under pressure, Norton’s book arrives as something rarer than a good history: it arrives as a mirror.

Who Is Mary Beth Norton, and Why Does It Matter?

Norton is the Mary Donlon Alger Professor Emerita of American History at Cornell University, a past president of the American Historical Association (2018), and a Pulitzer Prize finalist. She spent more than four decades researching colonial America before writing this book – and it shows. Her earlier work illuminated women’s lives in the Revolutionary era (Liberty’s Daughters), gendered power in the founding (Founding Mothers & Fathers), and the Salem witch trials (In the Devil’s Snare). She has always been drawn to the people squeezed out of the triumphant narrative: women, loyalists, the doubters, the losers.

That scholarly instinct shapes 1774 from its first page. Norton is not here to celebrate the Founders. She is here to complicate them — to show that the path from colonial grievance to Continental Army was not a confident march but a stumbling, anguished, sometimes violent negotiation between people who disagreed profoundly about what loyalty, liberty, and law actually meant.

The Central Argument: 1774, Not 1776

Norton’s core claim is both elegant and disruptive: the American Revolution did not begin in 1776 with a Declaration. It began in 1774, in the sixteen messy, terrifying months between the Boston Tea Party (December 1773) and the battles at Lexington and Concord (April 1775). During those months, colonial political culture was irrevocably transformed. New institutions – committees of correspondence, provincial congresses, local enforcement committees – effectively replaced royal government across thirteen colonies. By the time the first shots were fired, the revolution in governance had already happened.

By early 1775, royal governors throughout the colonies informed colonial officials in London that they were unable to thwart the increasing power of the committees and their allied provincial congresses. The war did not create the revolution. The revolution made the war inevitable.

Norton also insists on a truth that American mythology has long suppressed: Americans today tend to look back on the politics of those days and see unity in support of revolution. That vision is false. The population was divided politically then, as now. Support for resistance was never unanimous. Loyalists were not simply British pawns or cowards – many were thoughtful, principled people who genuinely believed that reconciliation was possible and that mob rule was as dangerous as Parliamentary tyranny.

Counterintuitively, the proposal to elect a congress to coordinate opposition tactics came not from radical leaders but from conservatives who hoped for reconciliation with Britain. Loyalists to England, not the revolutionaries, were the most vocal advocates for freedom of the press and strong dissenting opinions. London’s shortsighted responses kept pushing these moderates into the revolutionary camp – not because radicals won the argument, but because the British kept losing it for them.

The Author’s Voice: Close, Careful, and Unsparing

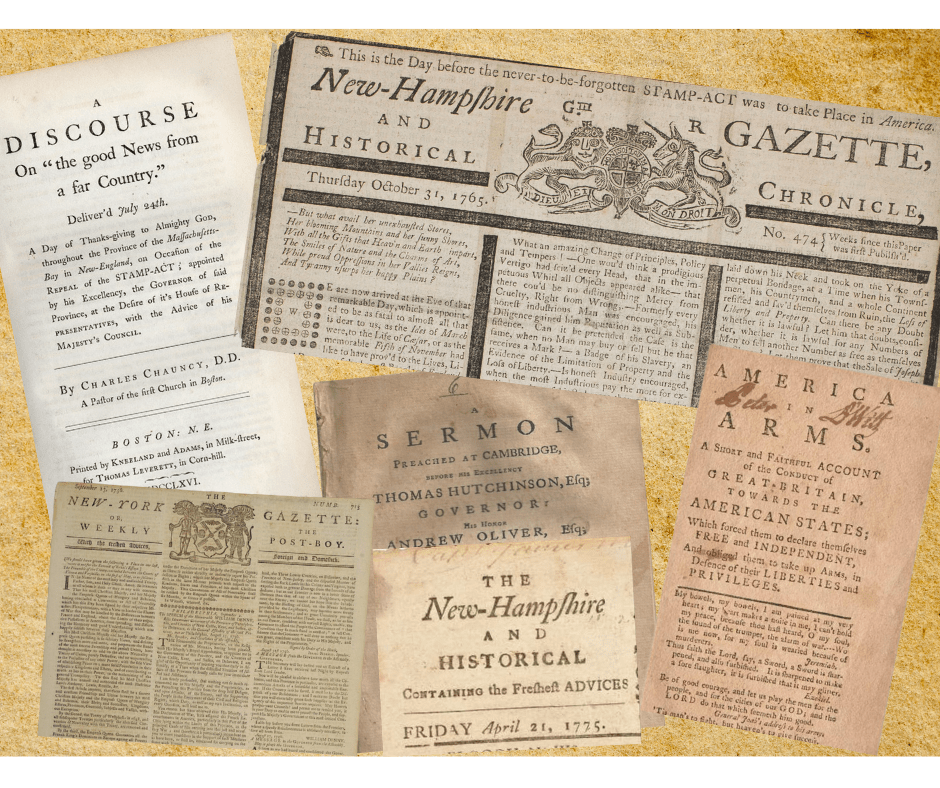

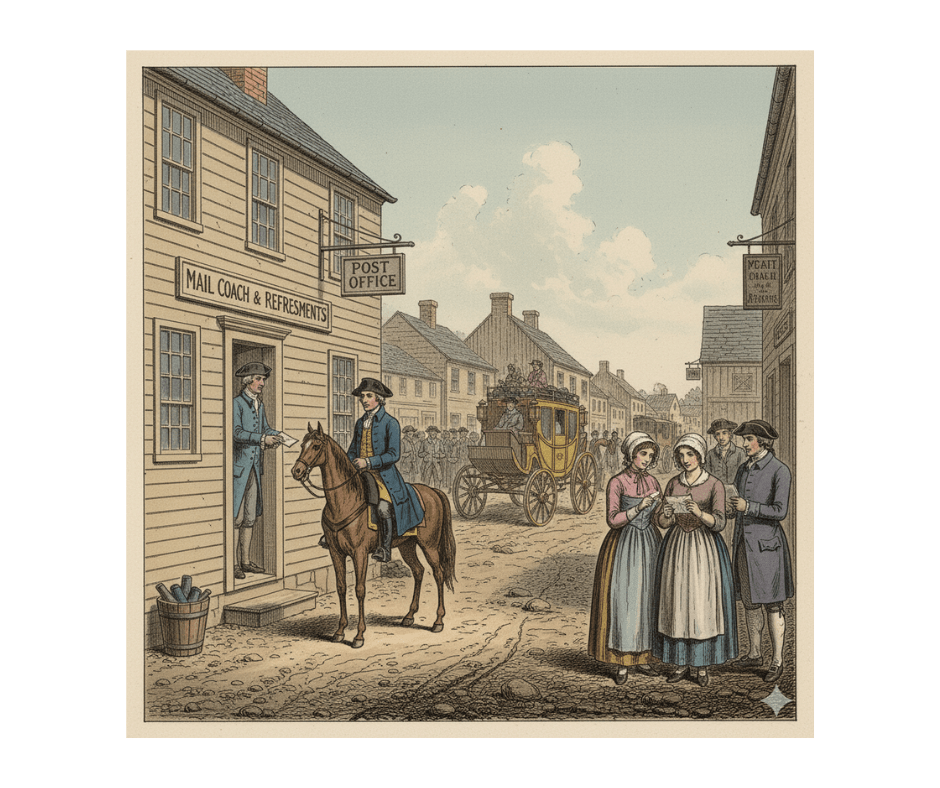

Norton’s prose is dense with primary sources – pamphlets, newspapers, diaries, letters – and she trusts them to speak. She reconstructs colonial political discourse in something close to real time, which creates an unusual and valuable effect: the reader does not know how things will turn out, because the people living through events did not know either. As the New York Review of Books observed, she “reminds us that even when it seemed inevitable that continuing protest would lead to violent confrontation with British troops, there were intelligent, articulate people in America who wanted desperately to head off the crisis.”

The tea economy alone gets a riveting treatment. Boston alone brought in 265,000 pounds of taxed tea in 1771 – but another 575,000 pounds of smuggled tea. Norton tracks tea not just as a commodity but as a political litmus test: what you drank, and where you bought it, announced your loyalties as clearly as any pamphlet. When women – so often excluded from formal political discourse – chose whether to serve tea at social gatherings, they were making public political statements. Norton pays attention to these choices. She is the rare colonial historian who does not treat gender as an afterthought.

Dialogue with the Series: Agreements and Arguments

Readers who have followed this “Booked for the Revolution” series will find Norton in productive conversation – and sometimes sharp disagreement – with the books we have examined previously. The most illuminating contrast is with Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967), still the towering intellectual framework for understanding why colonists rebelled. Bailyn argued that a coherent “Country” ideology – rooted in English radical Whig thought and obsessed with the threat of tyrannical conspiracy – gave colonial resistance its internal logic and emotional urgency. Norton does not dispute Bailyn’s intellectual architecture. But where Bailyn reconstructs the revolution from pamphlets and the minds of articulate men, Norton reconstructs it from committee minutes, newspaper letters, and the choices of people who were neither philosophers nor firebrands. Bailyn explains what colonists thought; Norton shows what they did – and how terrifying, coercive, and improvisational doing it actually was.

Gordon Wood’s compact The American Revolution: A History (2002) offers a complementary foil. Wood is the master of the long view: he shows how the Revolution unleashed democratic energies that eventually overwhelmed the very gentry class that launched it. His story arcs beautifully toward transformation. Norton’s story, by design, refuses that arc. She stops at the threshold – 1774 into early 1775 – and refuses to let the reader skip ahead to know how it all turns out. That discipline is precisely her point. The colonists living through 1774 did not know they were building a republic. They thought they were negotiating a crisis.

Robert Middlekauff’s The Glorious Cause (1982), the Oxford History of the United States volume covering the Revolution, provides the grandest traditional narrative against which to measure Norton. Middlekauff is comprehensive, authoritative, and deeply attentive to military history. But his frame is essentially Whiggish: the Revolution builds, the armies form, the cause prevails. Norton’s contribution is to slow that narrative to a near-standstill and examine the fault lines Middlekauff’s panoramic view necessarily blurs – the loyalists who were not villains, the moderates who were shoved rather than persuaded, the women whose tea choices were political acts. Where Middlekauff gives us the glorious cause, Norton gives us the anguished one.

Thomas Ricks’s First Principles (2020) enters this dialogue from a different angle, tracing how the Founders’ classical education – their immersion in Greek and Roman thought – shaped their vision of republican citizenship and civic virtue. Ricks’s Founders are self-consciously building something on ancient models. Norton’s colonists of 1774 are doing something more primitive and more urgent: they are improvising institutions on the fly, under pressure, with no Roman blueprint in front of them. Read together, the two books bracket the Revolution’s intellectual ambition against its messy political reality. Ricks shows what the Founders aspired to; Norton shows what they actually had to do to get there.

What We Have Learned Since 2020

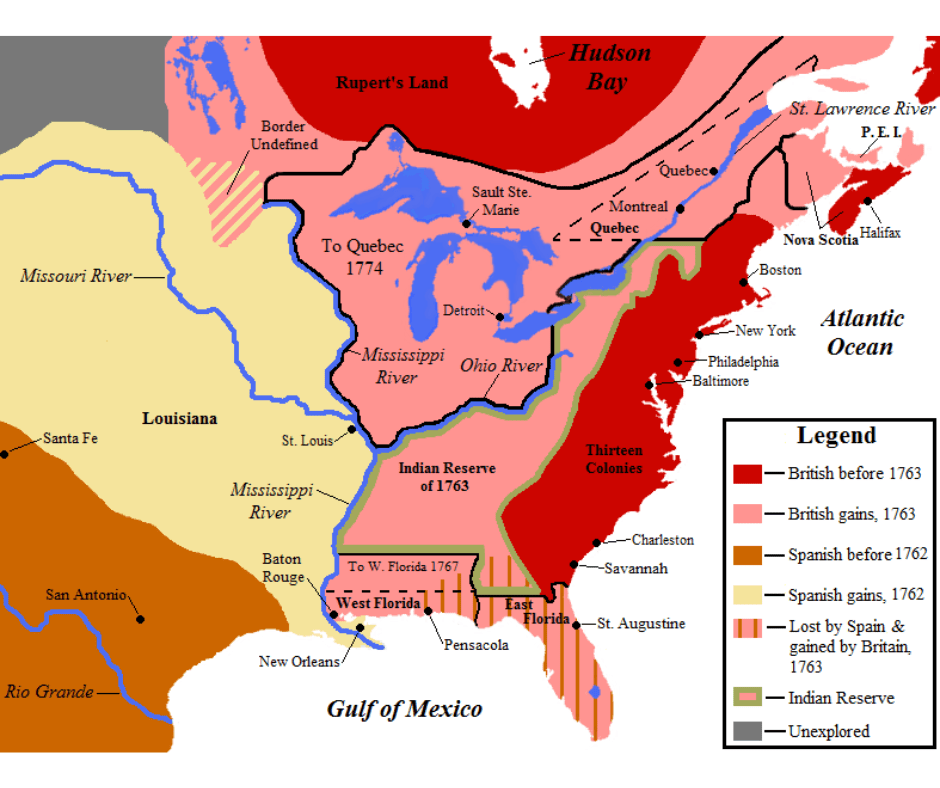

Published just before the pandemic and the national reckoning of 2020, 1774 has aged remarkably well – partly because Norton was already writing about political fracture, the fragility of institutions, and the violence that lurks beneath democratic argument. If anything, subsequent scholarship has deepened her themes. Historians of Native America have pressed further on how the crisis of 1774 reshaped Indigenous political calculations, particularly in the Ohio Valley, where both British officials and colonial committees were competing for alliances. And ongoing work in Atlantic history has strengthened Norton’s point that the loyalist perspective was not marginal but was, in many colonies, a majority position well into 1774.

The 250th anniversary commemorations of 1774’s key events – make Norton’s reframing newly urgent. Commemoration tends toward myth-making; Norton is the corrective.

Why Read This in 2026?

Because we live in a moment when political communities are fracturing, when the legitimacy of governing institutions is contested, and when ordinary people are being forced to choose sides they never anticipated choosing. Norton’s colonists are unnervingly familiar – not as heroes laying the groundwork for democracy, but as frightened, conflicted human beings trying to figure out what loyalty requires when the things they are loyal to are in contradiction with one another.

This important book demonstrates how opposition to the king developed and shows us that without the “long year” of 1774, there may not have been an American Revolution at all. More than that, it shows us how revolutions actually happen – not in a single dramatic moment of declaration, but in a thousand smaller moments of committee votes and canceled tea orders and midnight militia drills and neighbors who stop speaking to each other. It is not a comfortable book. It is an essential one.

A Note on This Series

This journey through Revolutionary history is as much about the evolution of historical understanding as the Revolution itself. History isn’t static – each generation reinterprets the past through its own concerns, asking different questions and prioritizing different sources. By reading these books in dialogue across 250 years, we’ll witness how scholarship evolves, how narratives get challenged, and how forgotten stories resurface.

This isn’t about declaring one interpretation “right” and another “wrong,” but appreciating the richness that emerges when multiple perspectives illuminate the same transformative moment. These books won’t provide definitive answers – history rarely does – but they equip us to think more clearly about how real people facing genuine uncertainty chose independence, how ideas had consequences, and how the work of creating a more perfect union continues. As we mark this anniversary, we honor the Revolutionary generation by reading deeply, thinking critically, and engaging seriously with both the brilliance and blind spots of what they created