January and February – Seeds of Rebellion Part Four

What do we mean by the Revolution? The war? That was no part of the Revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The Revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington. The records of the thirteen legislatures, the pamphlets, newspapers in all the colonies, ought to be consulted during that period to ascertain the steps by which the public opinion was enlightened and informed concerning the authority of Parliament over the colonies. – John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, 1815

When Americans argue today about government overreach, executive power, or the nature of liberty itself, they’re replaying a script written in the 1760s and 1770s. Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, first published in 1967, reveals something most of us never learned in school: the American Revolution wasn’t primarily about taxes or tea. It was about ideas – specifically, a coherent worldview about power, corruption, and the fragility of freedom that made independence seem not just desirable but absolutely necessary.

Reading Bailyn’s masterwork today feels unsettlingly contemporary. His revolutionaries obsessed over concentrated power, feared conspiracies against liberty, and believed a corrupt establishment was systematically undermining constitutional rights. Sound familiar? Understanding the intellectual framework that drove America’s founding becomes essential when those same concepts – often stripped of context – fuel our current political fires.

The Historian Who Changed How We Read Revolution

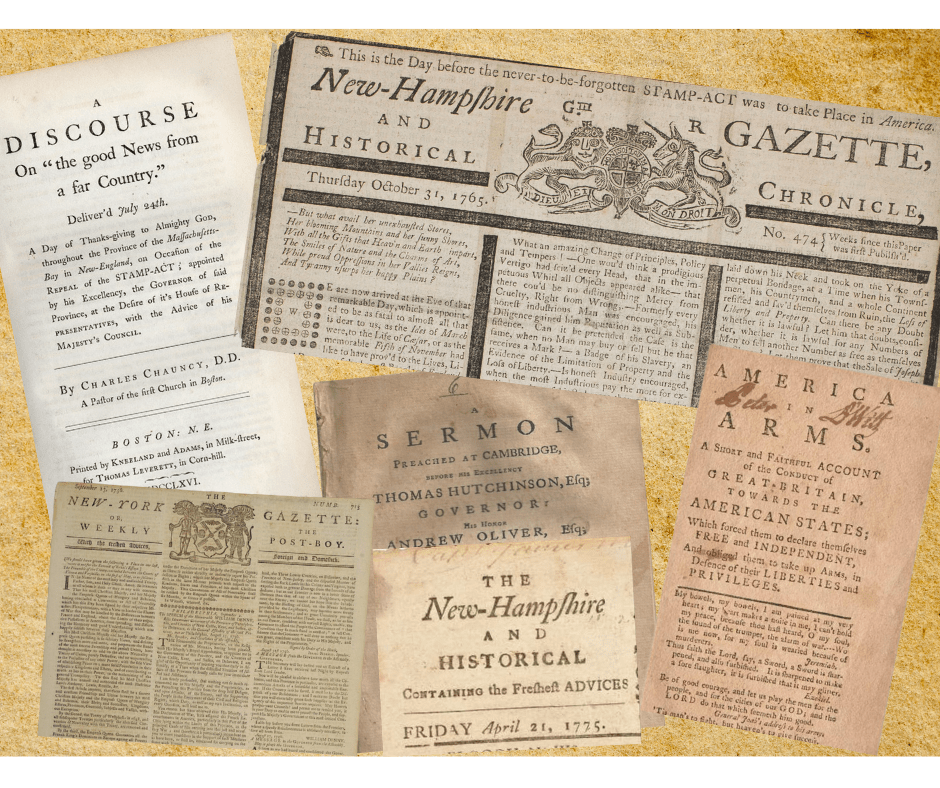

Bernard Bailyn, a Harvard historian who would win the Pulitzer Prize for this book, didn’t set out to write a conventional narrative of battles and heroes. Instead, he did something more radical: he actually read what ordinary colonists were reading. Diving into hundreds of pamphlets, sermons, and newspapers from the revolutionary era – sources historians had largely dismissed as propaganda – Bailyn discovered a sophisticated political ideology that had been hiding in plain sight.

Writing in the 1960s, during America’s own era of upheaval, Bailyn brought the precision of intellectual history to a moment often treated as inevitable march toward democracy. His timing mattered. As Americans questioned authority during Vietnam and the civil rights movement, Bailyn showed that the founders themselves were deeply skeptical of power, animated by ideas rather than merely economic grievances. This reframing transformed revolutionary scholarship and sparked decades of debate about what truly motivated America’s break with Britain.

Power Corrupts, Vigilance Protects: The Revolutionary Mindset

Bailyn’s central argument revolutionized our understanding of 1776. The colonists, he demonstrates, weren’t simply reacting to British policies they disliked. They had absorbed a specific tradition of political thought – what he calls “opposition ideology” – that taught them to interpret those policies as part of a deliberate plot to destroy their liberties.

This ideology emerged from several sources: classical writers like Cicero and Tacitus on republics and tyranny, Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke on natural rights and government by consent, English common law traditions, New England Puritanism’s emphasis on covenant and resistance to arbitrary authority, and especially the “radical Whig” writers of early eighteenth-century England who warned constantly about corruption and the abuse of power.

The last source proved most important. Writers like John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon (authors of Cato’s Letters) and the historian Catharine Macaulay weren’t mainstream voices in Britain, but they became gospel in America. They taught colonists a particular way of seeing politics: power constantly seeks to expand itself, those in authority inevitably become corrupted, liberty requires eternal vigilance, and seemingly small encroachments are actually part of larger conspiracies.

When Britain began tightening control after the Seven Years’ War – taxing the colonies, quartering troops, expanding vice-admiralty courts – Americans didn’t see practical adjustments to imperial administration. They saw confirmation of everything their reading had warned them about: a “systematic” plot to reduce them to slavery. Bailyn writes that the colonists believed they were witnessing “a comprehensive conspiracy against liberty throughout the English-speaking world – a conspiracy believed to have been nourished in corruption, and of which, it was felt, oppression in America was only the most immediately visible part.”

This wasn’t paranoia or exaggeration to Bailyn’s revolutionaries. Given their ideological framework, the pattern seemed clear and terrifying. The Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, the closure of Boston Harbor – each new measure fit perfectly into a template that predicted exactly this kind of creeping tyranny.

Voices From the Revolution

Bailyn lets the revolutionaries speak for themselves, and their words crackle with urgency. He quotes a 1768 letter describing how Americans understood their predicament: “The ministry have formed a systematick [sic] plan of reducing the northern colonies to absolute obedience to acts of Parliament… and if submitted to must end in the ruin of the colonies.” Notice the word “systematick” – not random policies but a coherent plan.

From the influential pamphleteer John Dickinson, Bailyn draws this passage about how tyranny arrives: “Nothing is wanted at home but a PRECEDENT, the force of which shall be established by the tacit submission of the colonies.” Rights, once surrendered, would never be recovered.

Perhaps most tellingly, Bailyn quotes the revolutionaries’ conviction that they weren’t radicals but conservatives, defending traditional British liberties against innovation and corruption. One writer proclaimed: “What do we want? Is it to be wantonly tearing up the foundation of our happy constitution? No. It is the preservation of it.” In their own minds, the British were the revolutionaries, destroying an ancient constitutional balance, while Americans defended eternal principles.

Bailyn also captures the religious dimension of revolutionary thought, quoting a Massachusetts election sermon that presented resistance as a sacred duty: “All the great Assertors of Liberty in all Ages have uniformly declared it to be unalienable.” Liberty came from God, not kings, and defending it became a moral imperative.

A New Interpretation Among Competing Narratives

Bailyn’s book entered a crowded field of revolutionary scholarship, and its ideological approach offered a distinct alternative to existing interpretations. The Progressive historians of the early twentieth century, particularly Carl Becker and Charles Beard, had emphasized economic motivations – class conflict, merchants protecting their interests, a revolution driven by “who shall rule at home” as much as home rule itself.

Bailyn didn’t deny economic factors but insisted they weren’t primary. Ideas mattered independently, shaping how colonists understood their material interests. Where Beard saw merchants manipulating ideology to serve their pocketbooks, Bailyn saw genuine believers whose worldview made certain policies intolerable regardless of their economic impact.

His work also complicated the consensus school of the 1950s, which portrayed Americans as fundamentally pragmatic and unideological. Bailyn showed revolutionaries possessed a sophisticated, coherent political theory that went far beyond pragmatic adjustment of interests.

More recently, Gordon Wood’s The Radicalism of the American Revolution extended Bailyn’s insights, arguing that the ideas Bailyn identified ultimately transformed American society more thoroughly than anyone intended, destroying aristocratic assumptions and creating genuinely democratic culture. Where Bailyn focused on the ideas that justified revolution, Wood traced how those ideas reshaped American life afterward.

Meanwhile, historians emphasizing social history and lived experience – like Gary Nash’s work on urban radicalism or Woody Holton’s research on how debt and economic pressures motivated backcountry farmers – provide necessary texture to Bailyn’s intellectual history. They remind us that while elite pamphleteers articulated opposition ideology, ordinary Americans had their own immediate grievances. The most complete picture likely combines Bailyn’s ideological framework with attention to how different groups experienced and deployed those ideas based on their particular circumstances.

What We’ve Learned Since 1967

Nearly sixty years after publication, scholarship has both confirmed and complicated Bailyn’s thesis. Research into the Atlantic world has shown how ideas circulated more complexly than Bailyn suggested, with influences running in multiple directions. Work on enslaved people and Native Americans has revealed how selectively revolutionary principles were applied – the ideology of liberty coexisted with slavery and dispossession, a tension Bailyn acknowledged but didn’t fully explore.

Historians have also questioned whether the conspiracy mindset was quite as coherent or universal as Bailyn suggested. Recent scholarship shows more variation in revolutionary thought across regions, classes, and religious communities. Not everyone read the same pamphlets or interpreted events through identical ideological lenses.

Yet Bailyn’s core insight endures: ideas genuinely mattered to the revolutionaries, and understanding their worldview is essential to understanding their actions. The challenge has been integrating his intellectual history with social, economic, and cultural approaches that illuminate how diverse Americans experienced revolution differently.

Perhaps most importantly, historians now better understand how revolutionary ideology’s emphasis on vigilance against power, fear of corruption, and suspicion of conspiracy became permanent features of American political culture – for better and worse. Bailyn identified the intellectual origins not just of revolution but of persistent American patterns: questioning authority, fearing centralized power, seeing politics in conspiratorial terms.

Why Read Bailyn in 2026?

In our current moment of polarization and institutional mistrust, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution offers essential perspective. When Americans across the political spectrum invoke founding principles, Bailyn helps us understand what those principles actually meant in their original context and how they functioned politically.

The book reveals that American political culture’s conspiratorial thinking, its suspicion of power, its emphasis on individual liberty against collective authority – these aren’t aberrations but features present from the beginning. Understanding this doesn’t resolve our debates, but it illuminates why we debate the way we do.

For anyone trying to understand why Americans talk about politics differently than citizens of other democracies, why we’re so suspicious of government power, why constitutional arguments dominate our political discourse, Bailyn provides the intellectual archaeology. The revolutionaries weren’t just our political ancestors; their ideology remains the grammar of American political argument.

The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution is dense but rewarding, written with clarity and packed with insight. It asks us to take ideas seriously – to consider that people really do act on political principles, not just material interests dressed up as principles. In our cynical age, that might be Bailyn’s most revolutionary suggestion of all.

A Note on This Series

This journey through Revolutionary history is as much about the evolution of historical understanding as the Revolution itself. History isn’t static – each generation reinterprets the past through its own concerns, asking different questions and prioritizing different sources. By reading these books in dialogue across 250 years, we’ll witness how scholarship evolves, how narratives get challenged, and how forgotten stories resurface.

This isn’t about declaring one interpretation “right” and another “wrong,” but appreciating the richness that emerges when multiple perspectives illuminate the same transformative moment. These books won’t provide definitive answers – history rarely does – but they equip us to think more clearly about how real people facing genuine uncertainty chose independence, how ideas had consequences, and how the work of creating a more perfect union continues. As we mark this anniversary, we honor the Revolutionary generation by reading deeply, thinking critically, and engaging seriously with both the brilliance and blind spots of what they created.