Part Four of #OctoberOnTheRoad

In the heart of North Carolina’s Piedmont region lies Salisbury, a city whose significance in American colonial and frontier history far exceeds what its modest size might suggest. As a crucial waypoint along the Great Wagon Road – the primary route for westward migration in 18th-century America – Salisbury emerged as a vital commercial, administrative, and cultural hub that helped shape the settlement patterns and development of the American South.

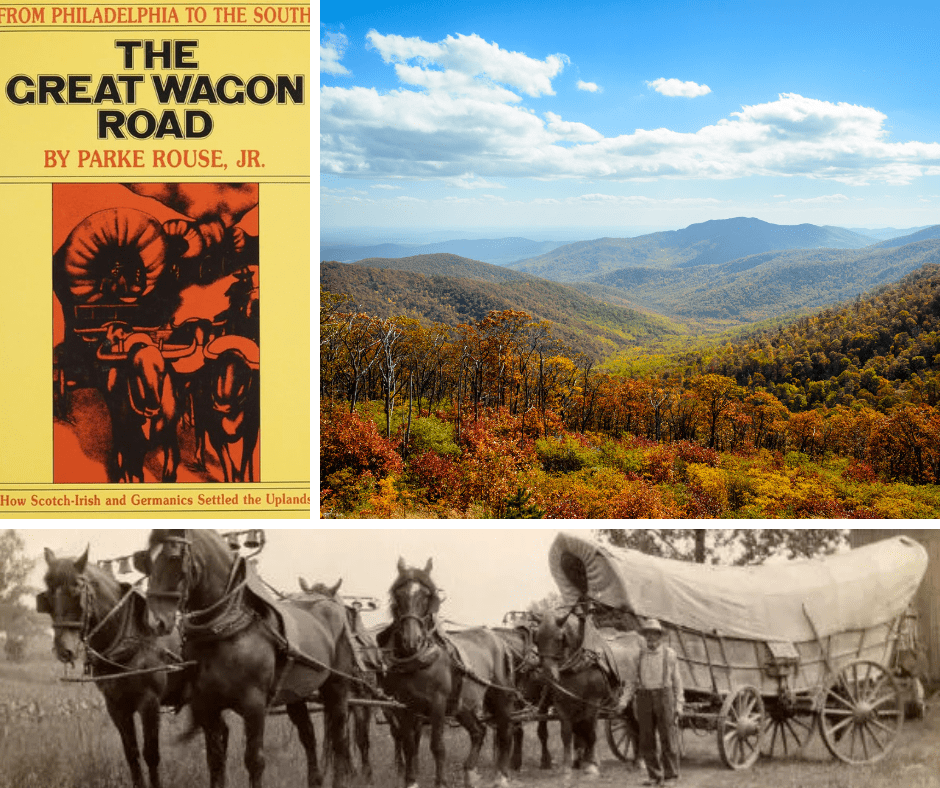

The Great Wagon Road: America’s First Highway

To understand Salisbury’s importance, one must first appreciate the monumental role of the Great Wagon Road itself. Stretching over 800 miles from Philadelphia through the Shenandoah Valley and into the Carolina Piedmont, this route served as the primary artery for migration and commerce during the colonial period. Between 1730 and 1775, an estimated quarter-million settlers traveled this road, making it arguably the most significant thoroughfare in pre-Revolutionary America. These migrants – predominantly Scots-Irish, German, and English settlers – were seeking fertile land and economic opportunity in the southern backcountry.

Strategic Establishment

Salisbury was officially established in 1753 as the county seat of Rowan County, which at the time encompassed a vast territory extending to the Mississippi River. The town’s location was no accident. Positioned at a strategic point where the Great Wagon Road crossed the Trading Path – an ancient Native American trail running east-west – Salisbury became a natural crossroads. This intersection of major routes transformed the settlement into an indispensable stop for travelers, traders, and settlers moving south and west.

The town was named after Salisbury, England, reflecting the British colonial influence, though its character would be shaped by the diverse stream of settlers flowing through on the wagon road. Its founders, including surveyor John Dunn, recognized the commercial potential of this location and deliberately planned a town that could serve the needs of the constant flow of migrants.

Before the official establishment, at least seven log homes already dotted the landscape. Among those early settlers was Johannes (John) Adams – evidence that these trails served as vital migration and trade corridors. Originally part of Anson County, the growing influx of families prompted the creation of Rowan County, with Salisbury designated as its county seat due to its thriving population.

The settlers brought more than farming traditions. Adams and his son, arriving from Lancaster, established themselves as potters – Adams purchased a lot in 1755 and became Salisbury’s first documented potter of European descent. Their lead-glazed earthenware reflected German ceramic traditions from Central Europe, contributing to North Carolina’s rich pottery heritage alongside influences from the Piedmont Quaker community and the Moravian settlement in Salem. Salisbury’s economy thus developed around both its geographic advantages and the specialized trades its settlers introduced.

John Adams died in 1762, and his sons evidently did not continue in the pottery trade. I am still trying to track down when they left Salisbury, but there is little doubt they did. There are no records of burials before 1793 in the Lutheran Cemetery, which means that John Adams was probably buried in an unmarked grave, possibly on the site of his log cabin.

Economic and Commercial Hub

As traffic along the Great Wagon Road intensified, Salisbury rapidly developed into a thriving commercial center. Taverns, inns, and ordinaries sprang up to accommodate weary travelers who needed rest, provisions, and their wagons repaired before continuing their journeys. Blacksmith shops, general stores, and trading posts proliferated, creating a bustling economy centered on serving the migration corridor.

The town became a crucial resupply point where settlers could purchase essential goods, livestock, and seeds before pushing farther into the frontier. Merchants in Salisbury established trade networks that connected the Atlantic seaboard with the developing backcountry, facilitating the flow of manufactured goods westward and agricultural products eastward. This commercial vitality attracted skilled craftsmen, professionals, and entrepreneurs, further diversifying the local economy.

Administrative and Political Significance

Beyond commerce, Salisbury served as an important administrative center for the sprawling North Carolina backcountry. As the county seat, it housed courts, government offices, and facilities that brought order to the frontier. The courthouse became a symbol of British authority and, later, American governance. Legal proceedings, land transactions, and official business conducted in Salisbury affected settlement patterns across a vast territory.

During the Revolutionary War, Salisbury’s strategic location made it militarily significant. The town served as a supply depot and recruiting center for Continental forces. Lord Cornwallis occupied Salisbury briefly in 1781 during his southern campaign, recognizing its importance as a logistics hub. The town’s prominence in the war effort underscored its role as a regional center of gravity.

Cultural Melting Pot

The constant flow of diverse settlers through Salisbury created a unique cultural environment. Scots-Irish Presbyterians, German Lutherans, English Anglicans, and others brought their distinct traditions, crafts, and worldviews. This diversity fostered a pragmatic, cosmopolitan atmosphere unusual for frontier settlements. Religious institutions, schools, and cultural organizations established in Salisbury served not just the town but the wider region, making it a center for learning and cultural development.

Lasting Legacy

While the Great Wagon Road’s importance diminished with the rise of railroads in the 19th century, Salisbury’s foundational role in regional development left an indelible mark. The town’s early prosperity enabled investment in infrastructure, education, and civic institutions that sustained its growth through subsequent eras. Today, Salisbury preserves numerous historic buildings and sites that tell the story of its wagon road heritage, including preserved sections of the Trading Path and 18th-century structures.

The city’s historic downtown reflects the layers of its past, from colonial-era foundations to antebellum architecture. Museums and heritage sites interpret the wagon road story for modern visitors, connecting present residents to this crucial chapter in American westward expansion.

Salisbury’s development along the Great Wagon Road exemplifies how geography and timing intersect to create places of outsized historical importance. As a crossroads of migration, commerce, and culture, this North Carolina town facilitated the settlement of the American South and helped write the story of a nation pushing westward toward its continental destiny.

And Now – A Twist!

All this month of October, I have been on a journey – physically and digitally – tracing the Adams family’s coming to North America before the founding of the United States of America. As I referenced in the introductory post, it has been a double-barreled journey of discovery: one focused on the Great Wagon Road’s strategic historical significance, and the other on solving the enduring mystery of my 2nd great-grandfather, John Washington Adams. The path beyond him is currently fractured into two intriguing, yet conflicting, ancestral branches.

This month has been the German branch, tracing a path from arrival in Philadelphia in 1727 to Lancaster and down the Great Wagon Road, arriving in Salisbury in the early 1750s. At this point, I’m going to have to find new resources and possibly take more physical trips to continue this journey.

However, during my research, I’ve come up on the possibility of another branch with English roots, and coming to North America in 1621!

While sharing all this with my brother, he made an interesting comment: I wonder if there are ever any conclusive genealogies that go back hundreds of years? I guess with “royalty” there is, but I’m guessing few lines among the peons have 100% certainty.

With that as a teaser, stay tuned for more in the future!

Part of a regular series on 27gen, entitled Wednesday Weekly Reader.

During my elementary school years one of the things I looked forward to the most was the delivery of “My Weekly Reader,” a weekly educational magazine designed for children and containing news-based current events.

It became a regular part of my love for reading, and helped develop my curiosity about the world around us.