We’ve come to the conclusion of a 5-part series of books about Mecklenburg County and Charlotte, NC during the years immediately preceding, and carrying through, the American Revolution – roughly 1765-1783. The final book – also the oldest, published in 1940 – is a work of fiction – but one that in my opinion provides an often missing part of understanding history.

Historical fiction serves as a vital bridge between past and present, transforming distant events and forgotten voices into vivid, accessible narratives that resonate with contemporary readers. Through the careful weaving of documented facts with imaginative storytelling, this genre breathes life into history’s dry statistics and dates, allowing us to experience the emotional truths of bygone eras through the eyes of characters who feel authentically human.

More than mere entertainment, historical fiction cultivates empathy by immersing readers in the struggles, triumphs, and daily realities of people from different times and cultures, fostering a deeper understanding of how historical forces shape individual lives. By illuminating the universal themes that connect us across centuries – love, loss, courage, and the pursuit of justice – historical fiction reminds us that while circumstances may change, the fundamental human experience remains remarkably constant, offering both perspective on our present challenges and hope for our shared future.

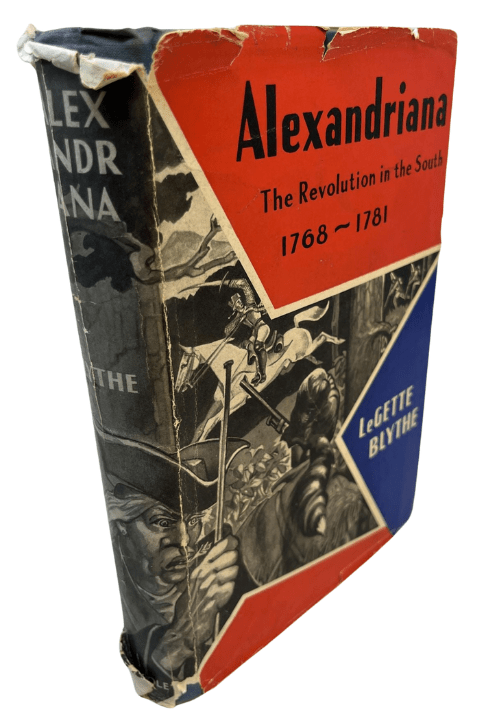

In Alexandriana, LeGette Blythe crafts a sweeping, nostalgic, and quietly patriotic novel that vividly resurrects colonial North Carolina on the eve of the American Revolution. First published in 1940, Alexandriana is both a regional romance and a work of historical fiction grounded in the lore surrounding Mecklenburg County’s bold – if disputed – claim to be the first American community to declare independence from Britain.

Though largely forgotten in modern literary circles, Blythe’s work deserves fresh attention, not only for its historical significance but for the way it captures a uniquely Southern imagination rooted in land, lineage, and the lingering hope of liberty.

Set in the early 1770s, Alexandriana follows the fictional life of David Barksdale, a spirited young man growing up on the prosperous John McKnitt Alexander plantation near present-day Charlotte. Named “Alexandriana”, the home stands as a symbol of frontier civility and classical refinement in a still-wild land. The novel follows Barksdale’s involvement in many events and battles both preceding and throughout the years of the American Revolution. His persona reflects the emerging tide of revolutionary thought sweeping the Carolina backcountry.

The novel opens in a world still ruled by British custom, Anglican orthodoxy, and class hierarchy. Barksdale is a “bound” boy – a form of apprenticeship. Throughout the years of the novel he grows from a shy boy to an educated young man. His father figure, John McKnitt Alexander, is depicted as the literal center of revolutionary thought in the county – secret meetings with fellow patriots, rumors of rebellion, and, eventually, involvement in what will be known as the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence.

Barksdale’s personal journey mirrors the broader political transformation of the region. He is shown to be sympathetic to the cause of liberty from the outset, influenced by Alexander’s passion, the injustices he witnesses under British rule, and the writings of well-known “revolutionaries” of the time. When war finally breaks out, Alexandriana becomes both a sanctuary and a battleground: a place where love, loss, and loyalty are all tested.

As the revolution accelerates, the novel becomes more dramatic. Skirmishes erupt. Families are torn apart by divided allegiances. Barksdale himself faces danger and heartbreak, from almost being hung as a traitor by English soldiers to escaping capture when lured by a forbidden love. As the novel proceeds, almost every historical figure involved in the battles in and around the Charlotte area are introduced and developed. Signers of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, Regulators, English commanders – even a young Andrew Jackson (from nearby Waxhaws) is fleshed out and brought to real life. The novel ends on an bittersweet note: independence is achieved, but at a great personal and communal cost. Alexandriana, both the homestead and the idea it represents, survives – but not without scars. Barksdale, now a young man, leaves his home of many years to marry the young woman introduced in the opening pages and teased throughout as beyond his reach.

LeGette Blythe, a North Carolina native and journalist, imbues Alexandriana with a deep affection for the region and its lore. The novel is richly atmospheric, with rolling descriptions of Carolina pine forests, rustic taverns, and parlor rooms filled with candlelight and the scent of a log fire. Blythe’s prose leans toward the romantic, evoking a wistful tone that matches the novel’s reverence for a lost world.

One of the novel’s most compelling strengths is its ability to humanize history. Rather than simply recount events like the the rumored May 20, 1775 declaration or the Mecklenburg Resolves, Blythe roots these moments in lived experience – arguments around supper tables, furtive whispers in barns, and agonizing decisions between loyalty and conscience. Barksdale’s coming-of-age arc gives readers an intimate view of how revolutions aren’t just fought on battlefields, but also in hearts and homes.

That said, the novel is unapologetically idealistic. Alexandriana itself is portrayed almost as an Eden – lush, orderly, cultured – run by benevolent landowners whose relationships with enslaved people are depicted in overly sentimental, unrealistic terms. As with many works of mid-20th-century Southern fiction, the institution of slavery is conspicuously softened. Though enslaved characters appear in the novel, they are relegated to the margins, rarely given full interior lives or moral agency. This romanticization reflects the blind spots of its time and warrants critical scrutiny by modern readers.

The same can be said for gender. While Barksdale’s two love interests are strong and thoughtful protagonists by the standards of the era, their agency is still circumscribed by patriarchal expectations. Their intellectual awakening is real, but their fates is ultimately tied to romantic and domestic fulfillment. Nevertheless, within these constraints, Blythe offers moments of genuine psychological insight. Barksdale’s internal struggle – between security and self-determination, decorum and defiance – feels authentic and earned.

Blythe’s historical detail is generally accurate, though he takes creative liberties to dramatize local legend. The Mecklenburg Declaration, which remains a subject of historical debate, is treated as fact in the novel. Yet this act of myth-making is part of the novel’s charm. Blythe isn’t trying to write academic history; he’s offering a literary defense of a community’s heroic self-conception. In doing so, he elevates local memory to the level of national meaning.

Alexandriana is a novel deeply rooted in time and place. While some of its portrayals are dated, its core themes – political awakening, the price of conviction, and the tension between tradition and transformation – remain relevant. For readers interested in Southern history, American independence, or the complexities of heritage and identity, Alexandriana offers a compelling, if imperfect, window into the birth of a nation from the Carolina frontier.

Like the homestead at its center, the novel is a blend of beauty and contradiction – elegant yet flawed, stirring yet shadowed. It invites both admiration and critique. And in that, perhaps, lies its enduring value.

Part of a regular series on 27gen, entitled Wednesday Weekly Reader.

During my elementary school years one of the things I looked forward to the most was the delivery of “My Weekly Reader,” a weekly educational magazine designed for children and containing news-based current events.

It became a regular part of my love for reading, and helped develop my curiosity about the world around us.

Note: Header art ©Dan Nance; LeGette Blythe photo ©Charlotte Mecklenburg Library