In a world obsessed with scrolling through TikTok and binging Netflix, who even thinks about libraries anymore? Well, Susan Orlean does, and her book, The Library Book, is basically a love letter to these amazing places. It’s not just about some dusty old books; it’s a deep dive into why libraries, even in our digital age, are still important.

The whole story kicks off with a bang – literally. Orlean starts by throwing us right into the chaos of the 1986 fire at the Los Angeles Central Library. Imagine a million books going up in smoke! It’s an intense scene, and Orlean makes you feel like you’re right there, watching the flames and the desperate efforts to save anything they could. But here’s the kicker: was it an accident, or did someone actually start this fire? This question leads Orlean down a wild path, introducing us to Harry Peak, a charming but unreliable guy who ended up being the prime suspect. It’s like Only Murders in the Building in book form, keeping you hooked while also showing how tricky it can be to figure out the real story.

But don’t think this book is just about a fire and a suspect. Orlean, who is well-known for this kind of deep-dive reporting, uses the fire as a jumping-off point to explore the whole history of libraries, especially the L.A. public system. She introduces us to a bunch of quirky characters who helped shape these places, from early librarians like Charles Lummis (who literally walked across the country to get a job there!) to the awesome folks keeping libraries going today. She shows us how libraries evolved from exclusive clubs where you had to pay to get in, to the open-to-everyone, democratic spaces we know today. It’s a fascinating look at how these places have always adapted to what people needed, whether it was a quiet place to read or a community hub.

Orlean also sprinkles in her own story, which makes the whole thing feel personal. She talks about going to the library with her mom as a kid, which totally sparked her lifelong love for books. This personal touch makes the facts and history feel more real and relatable. As she’s digging into the fire and the library’s past, you can feel her own connection to these places and the power of stories. Of course, her story tapped into mine, with lots of similar recollections and feelings.

Beyond all the history and personal tales, The Library Book makes a really strong case for why libraries still matter in our super-connected, digital world. Orlean doesn’t shy away from the challenges, like budget cuts and everyone just Googling everything. But she argues powerfully that libraries aren’t just about books anymore. They’ve become vibrant community centers, offering everything from help finding a job and getting immigration advice to cultural events and tech classes. They’re one of the last truly free and open spaces for everyone, no matter who you are or how much money you make. Think about it: where else can you just hang out, learn something new, and not have to pay a dime?

Orlean’s writing is captivating – she has this amazing way of making even the smallest details fascinating. She brings the library’s physical spaces to life: the smell of old paper, the quiet buzz of people studying, the passionate librarians. The Library Book isn’t just a list of facts; it’s an experience, pulling you into the heart of what makes libraries so incredibly special.

This book is basically a big love letter for knowledge, community, and bouncing back from tough times. It reminds us that libraries aren’t just buildings full of books; they’re living, breathing places that are constantly changing, reflecting our human need to learn, connect, and keep our stories alive. In a world drowning in info, Orlean’s awesome book is a perfect reminder of how valuable these quiet, yet powerful, treasures really are.

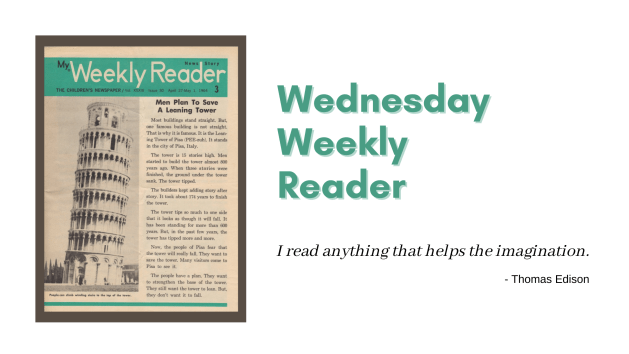

Part of a regular series on 27gen, entitled Wednesday Weekly Reader.

During my elementary school years one of the things I looked forward to the most was the delivery of “My Weekly Reader,” a weekly educational magazine designed for children and containing news-based current events.

It became a regular part of my love for reading, and helped develop my curiosity about the world around us.