January and February – Seeds of Rebellion Part Two

As previously discussed, Taylor’s continental approach reveals that North America was never destined to become an English-speaking nation. For nearly three centuries, the outcome remained genuinely uncertain as Spanish, French, and British empires pursued radically different colonial strategies across the continent. Understanding why Britain ultimately gained the upper hand requires examining not triumphalist inevitability, but the specific demographic, economic, and military factors that determined outcomes among competing visions of what “America” would become. Each empire brought distinct goals and methods to colonization, creating what Taylor describes as “new worlds compounded from the unintended mixing of plants, animals, microbes, and peoples on an unprecedented scale.” By the mid-eighteenth century, these competing imperial projects had produced dramatically different results – setting the stage for the dramatic events that would culminate in the American Revolution.

When European powers first cast their eyes westward across the Atlantic in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, North America represented an almost unimaginable prize: vast territories, untapped resources, and the promise of wealth and strategic advantage. Three nations – Spain, France, and Britain – would emerge as the dominant colonial powers on the continent, each pursuing distinctly different strategies shaped by their unique motivations, resources, and relationships with indigenous peoples.

Spain: The Pioneer of Empire

Spain arrived first and dreamed biggest. Emboldened by Christopher Columbus’s voyages and driven by the spectacular wealth extracted from Mexico and Peru, Spanish conquistadors and missionaries pushed northward into what is now the American Southwest and Southeast. Their colonial model was one of extraction and conversion: find precious metals, establish missions to convert Native Americans to Catholicism, and create a hierarchical society that mirrored the rigid class structures of Spain itself.

Spanish colonization followed the pathways of rumor and hope. Expeditions like those of Hernando de Soto through the Southeast and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado into the Southwest sought cities of gold that existed only in imagination. What they established instead was a chain of missions, presidios (military forts), and small settlements stretching from Florida through Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and into California. St. Augustine, founded in 1565, became the first permanent European settlement in what would become the United States – predating Jamestown by more than four decades.

However, Spain’s North American colonies never matched the wealth of its holdings farther south. The indigenous populations were smaller and more dispersed than in Mesoamerica, and the fabled gold never materialized in significant quantities. Spanish settlements remained thinly populated, heavily dependent on a coercive labor system that exploited Native Americans, and primarily served as defensive buffers protecting the more valuable territories of New Spain. By the eighteenth century, Spanish colonization had created an impressive geographic footprint but lacked the demographic and economic dynamism that would prove crucial in the imperial competition ahead.

France: Masters of the Interior

France took a different approach entirely. Rather than establishing densely populated agricultural colonies, French explorers and traders penetrated deep into the continental interior, following the St. Lawrence River, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi River system. From Quebec, founded in 1608, French influence spread westward and southward, creating a vast arc of territory that technically stretched from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

The French colonial model was built on adaptation and alliance. French traders, particularly the coureurs de bois (runners of the woods), integrated themselves into indigenous trading networks, often marrying Native American women and adopting local customs. The fur trade became the lifeblood of New France, exporting beaver pelts and other furs to insatiable European markets. Jesuit missionaries worked to convert indigenous peoples, though often with more respect for existing cultures than their Spanish counterparts demonstrated.

This approach had significant advantages. France maintained generally stronger alliances with Native American nations than either Spain or Britain, and French traders could operate across enormous distances with relatively small numbers. The downside was demographic: New France remained perpetually underpopulated. While British colonies attracted hundreds of thousands of settlers, French Canada struggled to grow beyond about 70,000 residents by the mid-eighteenth century. France’s colonial policies, which discouraged Protestant Huguenots from emigrating and focused settlement efforts on urban centers rather than agricultural expansion, meant that New France commanded vast territories but lacked the population to defend them effectively.

Britain: The Power of Numbers

British colonization began haltingly with the establishment of Jamestown in 1607 and Plymouth in 1620, but it accelerated rapidly throughout the seventeenth century. Unlike Spain’s extraction model or France’s trading networks, Britain’s colonies were fundamentally settlements – places where English, Scots-Irish, German, and other European migrants came to establish permanent communities, cultivate land, and recreate (or reimagine) the societies they had left behind.

The diversity of British colonization was remarkable. New England developed around Puritan religious communities, small-scale farming, fishing, and eventually maritime commerce and shipbuilding. The Middle Colonies became breadbaskets of grain production and models of relative religious tolerance. The Southern Colonies built plantation economies dependent on tobacco, rice, and indigo, increasingly reliant on enslaved African labor. This economic diversity created resilience and interconnected markets that strengthened the colonial system as a whole.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the British colonies boasted populations exceeding one million – dwarfing their French rivals and rendering Spanish Florida and the Southwest demographically insignificant by comparison. This population advantage translated into economic productivity, military manpower, and an ever-expanding hunger for land that pushed inexorably westward into territories claimed by France and inhabited by Native American nations.

Britain’s Ascendancy: Why the English Prevailed

Several factors explain Britain’s dominant position by the 1760s. First and most important was demography. The sheer number of British colonists created facts on the ground that neither French traders nor Spanish missionaries could match. More people meant more cleared land, more towns, more economic production, and more soldiers when conflicts arose.

Second, Britain’s constitutional system, for all its flaws, created a more dynamic economy than the absolutist monarchies of France and Spain. Property rights were better protected, entrepreneurship was encouraged, and colonial assemblies gave settlers a stake in their own governance that fostered loyalty and investment. The Navigation Acts tied colonial economies to Britain, but they also guaranteed markets and naval protection.

Third, British naval supremacy proved decisive. The Royal Navy could project power, protect maritime commerce, and prevent French and Spanish reinforcement of their colonies during wartime. The series of imperial wars culminating in the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) demonstrated this advantage repeatedly.

Finally, Britain benefited from the weaknesses of its rivals. Spain’s empire was overextended and increasingly ossified. France faced the impossible task of defending an enormous territory with inadequate population and resources, particularly when facing Britain’s combination of naval power and demographic advantage.

The Irony of Success

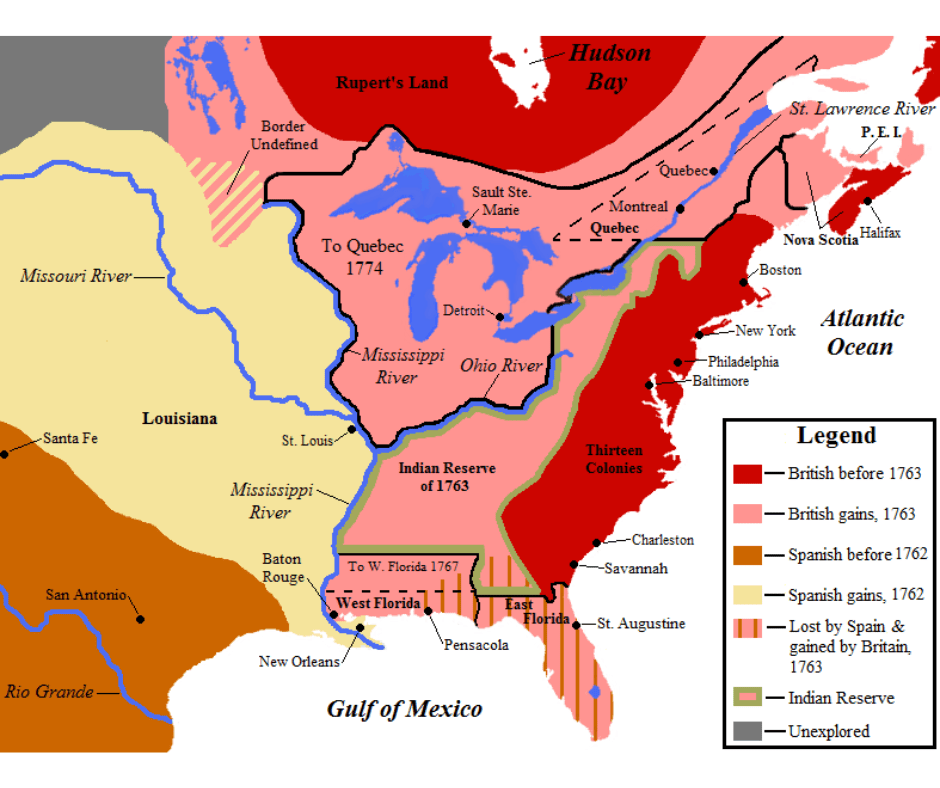

The Treaty of Paris in 1763, ending the Seven Years’ War, marked the zenith of British power in North America. France ceded Canada and its claims east of the Mississippi. Spain surrendered Florida. Britain stood supreme, master of the Atlantic seaboard and beyond.

Yet this very success contained the seeds of imperial crisis. The war had been expensive, and Britain expected its prosperous colonies to help pay the costs. The colonists, having helped win the war and no longer facing French threats, increasingly questioned why they needed British rule at all. The very demographic and economic dynamism that had made the British colonies strong now made them confident and restive.

Britain had won the race for North America, but in doing so, it had created colonies powerful enough to imagine independence. The path to revolution would emerge not from weakness, but from strength – the ultimate irony of imperial triumph.

A Note on This Series

This journey through Revolutionary history is as much about the evolution of historical understanding as the Revolution itself. History isn’t static – each generation reinterprets the past through its own concerns, asking different questions and prioritizing different sources. By reading these books in dialogue across 250 years, we’ll witness how scholarship evolves, how narratives get challenged, and how forgotten stories resurface.

This isn’t about declaring one interpretation “right” and another “wrong,” but appreciating the richness that emerges when multiple perspectives illuminate the same transformative moment. These books won’t provide definitive answers – history rarely does – but they equip us to think more clearly about how real people facing genuine uncertainty chose independence, how ideas had consequences, and how the work of creating a more perfect union continues. As we mark this anniversary, we honor the Revolutionary generation by reading deeply, thinking critically, and engaging seriously with both the brilliance and blind spots of what they created.