The famous battles that form the backbone of the story put forth of American independence – at Lexington and Concord, Brandywine, Germantown, Saratoga, and Monmouth – while crucial, did not lead to the surrender at Yorktown.

It was in the three-plus years between Monmouth and Yorktown that the war was won.

Alan Pell Crawford’s riveting new book,This Fierce People, tells the story of these missing three years, long ignored by historians, and of the fierce battles fought in the South that made up the central theater of military operations in the latter years of the Revolutionary War, upending the essential American myth that the War of Independence was fought primarily in the North.

Weaving throughout the stories of the heroic men and women, largely unsung patriots – African Americans and whites, militiamen and “irregulars,” patriots and Tories, Americans, Frenchmen, Brits, and Hessians, Crawford reveals the misperceptions and contradictions of our accepted understanding of how our nation came to be, as well as the national narrative that America’s victory over the British lay solely with General George Washington and his troops.

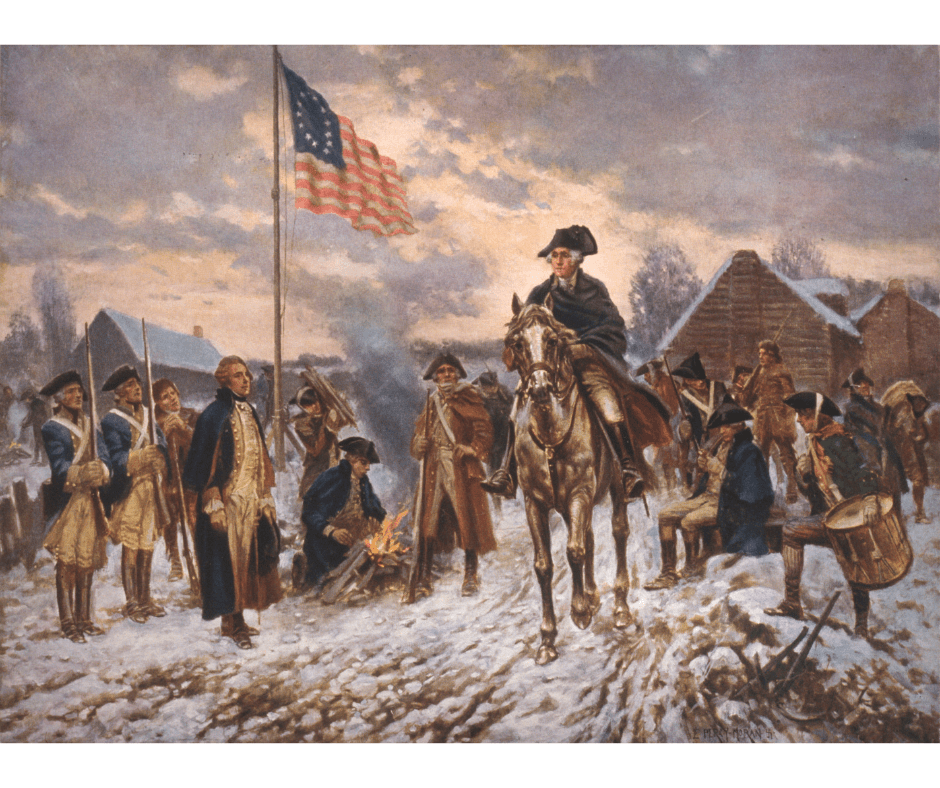

The American Revolutionary War holds a revered place in the nation’s collective memory, often depicted as a heroic struggle led by George Washington against the mighty British Empire. This narrative, deeply ingrained in American culture, typically focuses on the war’s northern theater, highlighting iconic moments such as the battles of Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, Washington’s crossing of the Delaware, and the harsh winter at Valley Forge. However, this perspective, while stirring, presents an incomplete and potentially misleading account of the conflict that birthed a nation.

The Washington-Centric Narrative

The dominance of this northern-focused, Washington-centric narrative can be traced back to the early years of the republic. Biographies of George Washington, such as Parson Weems’s The Life of George Washington (1808) and John Marshall’s similarly titled work (1838), played a significant role in shaping public perception. These accounts, naturally centered on Washington’s experiences, emphasized events in which he was directly involved or closely associated. This trend continued with Washington Irving’s five-volume biography in 1855, further cementing the focus on the northern theater of the war.

Even contemporary histories written in the early 19th century, such as those by William Moultrie (1802) and Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee III (1812), which provided valuable insights into other aspects of the war, never achieved the widespread readership of the Washington biographies. Additionally, early histories of the young nation, like that of Mercy Otis Warren (1805), were often written by New Englanders, inherently biasing the narrative towards events in that region.

The Overlooked Southern Campaign

This established narrative, however compelling, overlooks a crucial fact: much of the war, including some of its most decisive battles, took place in the South. The events that ultimately forced the British to surrender at Yorktown in 1781 largely occurred in the southern states, far from Washington’s direct command. Ironically, Washington himself did not cross the Potomac until the late summer of 1781, more than three years after the last major battle in the North at Monmouth.

The southern campaign of the Revolutionary War is rich with dramatic events and compelling figures that deserve recognition. Battles such as Camden, Kings Mountain, and Cowpens played critical roles in shaping the war’s outcome, yet they remain unfamiliar to many Americans. The war in the South was not just a conflict between American Continentals and British redcoats; it was also a brutal civil war between “partisans” fighting for independence and their “loyalist” neighbors, marked by fierce battles, skirmishes, and acts of domestic terrorism.

Factors Contributing to the Oversight

Several factors have contributed to the relative neglect of the southern campaign in popular and academic histories:

- Early Historiography: The earliest accounts of the war, primarily biographies of Washington, naturally focused on his direct experiences in the northern theater.

- Regional Bias: Many early histories were written by New Englanders, leading to a focus on events in that region.

- Civil War Legacy: In the aftermath of the Civil War, historians were reluctant to celebrate the contributions of southerners to the Revolutionary War, given the recent conflict.

- Loyalty Concerns: Even in the early years of the republic, the presence of loyalist elements in the South during the Revolutionary period made some historians wary of emphasizing the region’s role.

- Slavery: Perhaps most significantly, the fact that many southern Revolutionary leaders and soldiers were slaveholders has made modern historians hesitant to celebrate their contributions to the cause of independence.

The Complexity of the Southern Theater

The southern campaign of the Revolutionary War presents a complex and sometimes uncomfortable narrative. It involves slaveholders fighting for their own liberty while denying it to others, a contradiction that was apparent even to contemporaries. Samuel Johnson famously asked, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of negroes?”

This complexity extends to the involvement of African Americans in the war. They fought on both sides of the conflict and, when denied the opportunity to fight, served as laborers and servants. The record of slavery and abolitionism during this period is not as straightforward as later generations might wish. There were abolitionists in the South and slaveholders in the North, including such notable figures as Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton.

Some southern leaders, including Thomas Jefferson and Henry Laurens, acknowledged the moral wrongness of slavery, viewing it as a violation of the very values for which the Revolution was fought. However, they remained compromised by their continued ownership of slaves and inability to devise practical plans for abolition.

The Need for a More Complete History

Despite these complexities – or perhaps because of them – it is crucial to reassess and more fully incorporate the southern campaign into our understanding of the Revolutionary War. Doing so does not require diminishing Washington’s role or the significance of the northern campaign. Indeed, it can enhance our appreciation of Washington’s leadership, particularly his ability to recognize and trust the abilities of commanders like Nathanael Greene and Daniel Morgan to conduct the war in the South.

A more complete history of the Revolutionary War would reveal that the South had its own “embattled farmers” and “citizens in arms,” its own heroic figures like the “Molly Pitchers” of northern lore. It would acknowledge the civil war aspect of the conflict in the South, with its attendant brutality and complexity. It would also grapple with the uncomfortable truth that many of the southern leaders fighting for independence were themselves slaveholders, some even slave traders.

The standard narrative of the American Revolutionary War, focused primarily on Washington and the northern theater, while inspiring, fails to capture the full scope and complexity of the conflict that gave birth to the United States. By expanding our view to include the crucial southern campaign, we can gain a more nuanced and accurate understanding of the war, its participants, and its legacy.

This broader perspective allows us to appreciate the contributions of often-overlooked figures and regions to the cause of independence. It also forces us to confront the contradictions and moral complexities inherent in the Revolutionary period, particularly regarding the institution of slavery. While it may be uncomfortable to acknowledge that many of those fighting for liberty were themselves denying it to others, it is essential for a full and honest reckoning with our nation’s history.

As we continue to seek a “usable past” in the story of the American Revolution, we must strive for a narrative that encompasses the full geographical and moral landscape of the conflict. Only by doing so can we truly understand the origins of our nation and the ongoing struggle to live up to its founding ideals.

Part of a regular series on 27gen, entitled Wednesday Weekly Reader.

During my elementary school years one of the things I looked forward to the most was the delivery of “My Weekly Reader,” a weekly educational magazine designed for children and containing news-based current events.

It became a regular part of my love for reading, and helped develop my curiosity about the world around us.