The journey through midlife (ages 45-65) often brings us to an unexpected crossroads – one where we’re invited to transform our relationship with success, purpose, and personal growth. While our earlier years might have been dominated by external measures of achievement (what we do, what others think, what we own, and what we control), midlife presents an opportunity for a profound shift in perspective.

Developmental psychologist Erik Erikson suggests a powerful alternative mindset: “I am what survives me.” This simple yet profound reframing encourages us to consider our legacy and impact on future generations, moving beyond immediate gratification to focus on lasting contribution.

Think of yourself as a plant that occasionally needs repotting to flourish. Throughout our careers, we accumulate valuable seeds of knowledge and wisdom. Midlife offers the perfect opportunity to transplant these seeds into new soil, allowing us to grow in different directions. With decades of experience, we’re better equipped to recognize the environments where our talents will thrive.

The modern workplace increasingly supports this evolution. The pandemic accelerated the trend toward flexible work arrangements, with more companies offering phased retirement options. This shift acknowledges that stepping back from full-time work doesn’t mean retiring completely – instead, it’s an invitation to reimagine how we can apply our skills and knowledge in new ways.

One of the most valuable contributions older professionals can make is teaching and mentoring. As Arthur C. Brooks notes, the best synthesizers and explainers of complex ideas tend to be in their mid-60s or older. This makes intuitive sense – wisdom accumulated over decades creates natural teachers. Beyond technical expertise, older professionals offer “invisible productivity” – the ability to elevate the performance of entire teams through their well-developed social skills and emotional intelligence.

The key to thriving in this new chapter lies in becoming a beginner again. While it might seem counterintuitive to start fresh when you’ve mastered certain skills, introducing novelty into your life creates distinct memories and actually slows down your perception of time. When we engage in new activities that put us in a state of flow, we temporarily lose track of time, creating a psychological pause in aging.

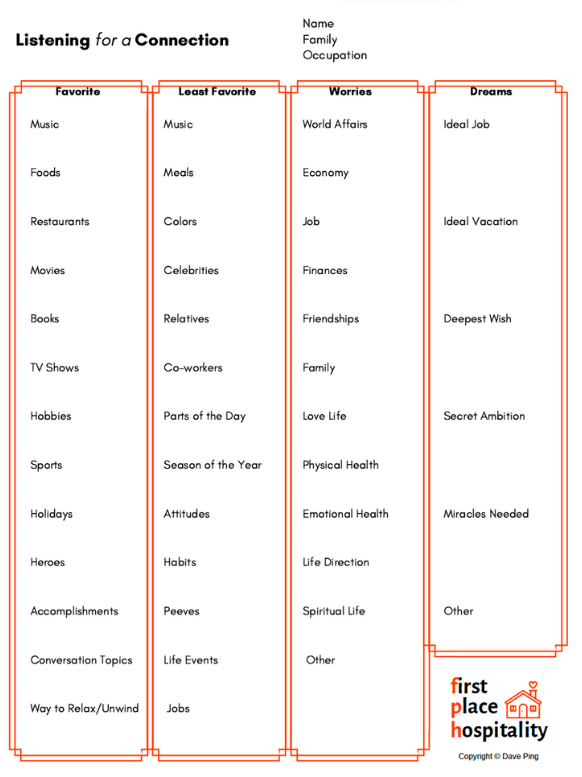

Curiosity plays a crucial role in this reinvention process. Like hunger or thirst, curiosity creates a dopamine-fueled motivation to seek information and learn. Particularly valuable is what author Jeff Wetzler calls “connective curiosity” – the desire to understand others’ thoughts, experiences, and feelings. This form of curiosity, rooted in the Latin word for “care,” becomes an act of genuine interest in others that deepens relationships and learning opportunities.

To maintain your curiosity, practice what Simon T. Bailey calls “vujá dé” – the opposite of déjà vu. This means seeing familiar situations with fresh eyes and understanding common experiences in new ways. It’s about finding extraordinary insights in ordinary moments through careful observation and openness to new perspectives.

I’m reminded of a quote by Alexandra Horowitz: In childhood, then, attention is brightened by two features: children’s neophilia (love of new things) and the fact that, as young people, they simply haven’t seen it all before.

Can you learn to have the curiosity of a child again?

Having rediscovered this curiosity, what does that mean for our legacy?

Most of us want to leave a legacy, even in the smallest ways. Here are five questions that could help define your legacy:

- Who will benefit most from what you leave behind?

- What invisible but valuable gifts can you offer?

- How will you prepare and deliver your legacy?

- When is the most meaningful time to share your wisdom?

- Why does this matter to you personally?

Here’s some wisdom from David Viscott: “The purpose of life is to discover your gift. The work of life is to develop it. The meaning of life is to give your gift away.” Midlife isn’t about retiring from life – it’s about transitioning from “human doing” to “human being.” It’s an opportunity to move beyond the pursuit of happiness to the practice of joy, finding fulfillment in sharing your accumulated wisdom and experience with others.

My journey of becoming a Modern Elder involves embracing both the wisdom I’ve gained and the beginner’s mind that keeps me growing. By maintaining my curiosity, seeking new challenges, and focusing on meaningful contribution, I am creating a second half of life that’s as rich and rewarding as the first – perhaps even more so.

This transformation doesn’t happen automatically – it requires intentional effort to see familiar situations with new eyes and remain open to learning from others. Surrounding yourself with people who challenge your thinking and illuminate your blind spots helps maintain this growth mindset. As I continue to navigate this transition, I am reminded that my greatest contribution might not be in what I do, but in how I help others grow and develop through my accumulated wisdom and experience.