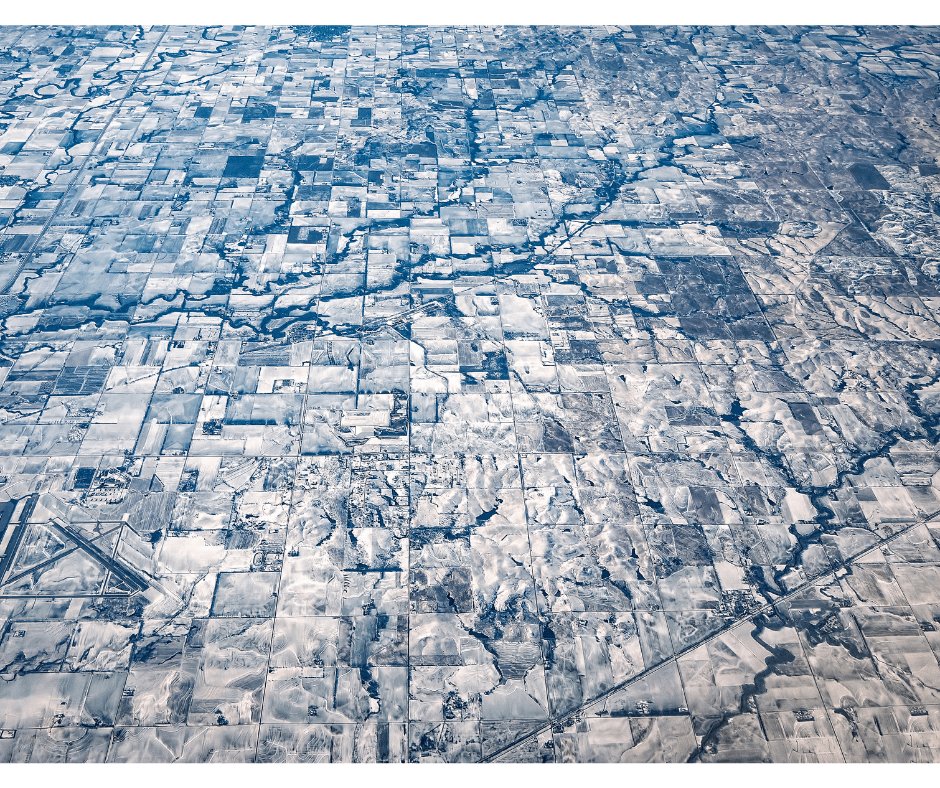

Seen from an airplane, much of the United States appears to be a gridded land of startling uniformity. Perpendicular streets and rectangular fields, all precisely measured and perfectly aligned, turn both urban and rural America into a checkerboard landscape that stretches from horizon to horizon. In evidence throughout the country, but especially the West, the pattern is a hallmark of American life. One might consider it an administrative convenience – an easy way to divide land and lay down streets – but it is not. The colossal grid carved into the North American continent, argues historian and writer Amir Alexander, is a plan redolent with philosophical and political meaning.

In 1784 Thomas Jefferson presented Congress with an audacious scheme to reshape the territory of the young United States. All western lands, he proposed, would be inscribed with a single rectilinear grid, transforming the natural landscape into a mathematical one. Following Isaac Newton and John Locke, he viewed mathematical space as a blank slate on which anything is possible and where new Americans, acting freely, could find liberty. And if the real America, with its diverse landscapes and rich human history, did not match his vision, then it must be made to match it.

From the halls of Congress to the open prairies, and from the fight against George III to the Trail of Tears, Liberty’s Grid tells the story of the battle between grid makers and their opponents. When Congress endorsed Jefferson’s plan, it set off a struggle over American space that has not subsided. Transcendentalists, urban reformers, and conservationists saw the grid not as a place of possibility but as an artificial imposition that crushed the human spirit. Today, the ideas Jefferson associated with the grid still echo through political rhetoric about the country’s founding, and competing visions for the nation are visible from Manhattan avenues and Kansan pastures to Yosemite’s cliffs and suburbia’s cul-de-sacs. An engrossing read, Liberty’s Grid offers a powerful look at the ideological conflict written on the landscape.

From the window of a commercial jetliner flying over the western United States, a striking pattern emerges: an endless succession of square fields, perfectly aligned with the compass points, stretching from horizon to horizon. This geometric tapestry covers two-thirds of the continental United States, imposing a uniform mathematical design upon the natural landscape. Mountains, valleys, rivers, and even cities bend to its will, creating a sight that is both awe-inspiring and perplexing.

This vast checkerboard is known as the Great American Grid, a unique feature of the American landscape that sets it apart from the rest of the world. While rectilinear patterns in agricultural land can be found in other parts of the globe, none match the scale, uniformity, and sheer ambition of the American grid. It is a single, unified network that redefines space itself, transforming a diverse continent into a uniform mathematical plane.

The origins of this grand design can be traced back to one of America’s founding fathers: Thomas Jefferson. The same man who penned the Declaration of Independence also conceived of and championed the idea of dividing the entire continent into regular squares. Far from being a mere practical convenience for land transactions, the grid was a bold ideological statement, embodying Jefferson’s vision of America as a land of unconstrained freedom and infinite opportunity.

Jefferson’s grid was not implemented without resistance. Even George Washington opposed the plan, arguing that it would hinder rather than facilitate settlement and expansion. The technical challenges of imposing a single Cartesian grid over such a vast landmass were immense, requiring a multigenerational effort by a dedicated government bureaucracy. This herculean task, conducted at the frontiers of technical feasibility, lasted nearly two centuries.

The grid’s implementation was driven by Jefferson’s belief in an “Empire of Liberty.” In his vision, the vacant and uniform mathematical terrain would provide a blank slate for enterprising settlers to build their fortunes and forge a nation, unconstrained by history, tradition, or geography. The grid became a physical manifestation of the American dream, promising limitless opportunity to all who ventured westward.

However, Jefferson’s vision was not universally embraced. As the grid spread across the western landscape, it faced opposition from those who viewed it with profound skepticism. Transcendentalists like Henry David Thoreau, urban reformers such as Frederick Law Olmsted, and conservationists like John Muir saw the rectilinear terrain not as a land of freedom, but as an oppressive artificial imposition.

These critics argued that the unchecked settlement of the West led not only to opportunities for settlers but also to the destruction of the natural environment and the displacement of indigenous peoples. They viewed the grid as a soulless mathematical construct that crushed the human spirit and set people on a path to social and moral degradation. Their solution was to check the spread of the Cartesian terrain by circumscribing it with naturalistic landscapes.

This ideological conflict between the grid and the “anti-grid” has shaped the American landscape into a terrain of contrasts. The rigid rectilinear cities give birth to naturalistic parks at their centers and curvilinear suburbs at their outskirts. The vast gridded expanse of the West is punctuated by protected natural wonders. The streets of Manhattan and the cornfields of Kansas stand in stark contrast to the winding paths of Central Park and the rugged cliffs of Yosemite Valley.

The battle between these competing visions continues to this day, with each side leaving its mark on the American landscape. The grid, with its promise of freedom and opportunity, remains a powerful symbol of the American dream. Yet the anti-grid, with its emphasis on harmony with nature and preservation of wilderness, serves as a constant reminder of the costs of unchecked expansion.

This ongoing conflict is more than just a matter of landscape design; it reflects fundamental tensions in the American psyche. The grid embodies the belief in progress, individualism, and the power of human ingenuity to shape the world. The anti-grid, on the other hand, represents a reverence for nature, a recognition of human limitations, and a desire for organic community.

As America continues to evolve, the interplay between these competing visions will undoubtedly shape its future. The great American grid, born from Jefferson’s mathematical mind and ideological convictions, remains a testament to the power of ideas to transform the physical world. It stands as a bold statement of what America aspires to be: a land of boundless opportunity where individuals can forge their own destinies.

Yet the presence of the anti-grid serves as a crucial counterbalance, reminding us of the importance of preserving natural beauty, respecting ecological limits, and maintaining a sense of humility in the face of nature’s grandeur. The tension between these two visions – the mathematical and the organic, the planned and the wild – continues to define the American landscape and the American character.

As we look to the future, the challenge lies in finding a balance between these competing ideals. Can we preserve the spirit of opportunity and innovation embodied by the grid while also respecting the natural world and the diverse communities that call this land home? The answer to this question will shape not only the American landscape but also the nation’s identity for generations to come.

Part of a regular series on 27gen, entitled Wednesday Weekly Reader.

During my elementary school years one of the things I looked forward to the most was the delivery of “My Weekly Reader,” a weekly educational magazine designed for children and containing news-based current events.

It became a regular part of my love for reading, and helped develop my curiosity about the world around us.