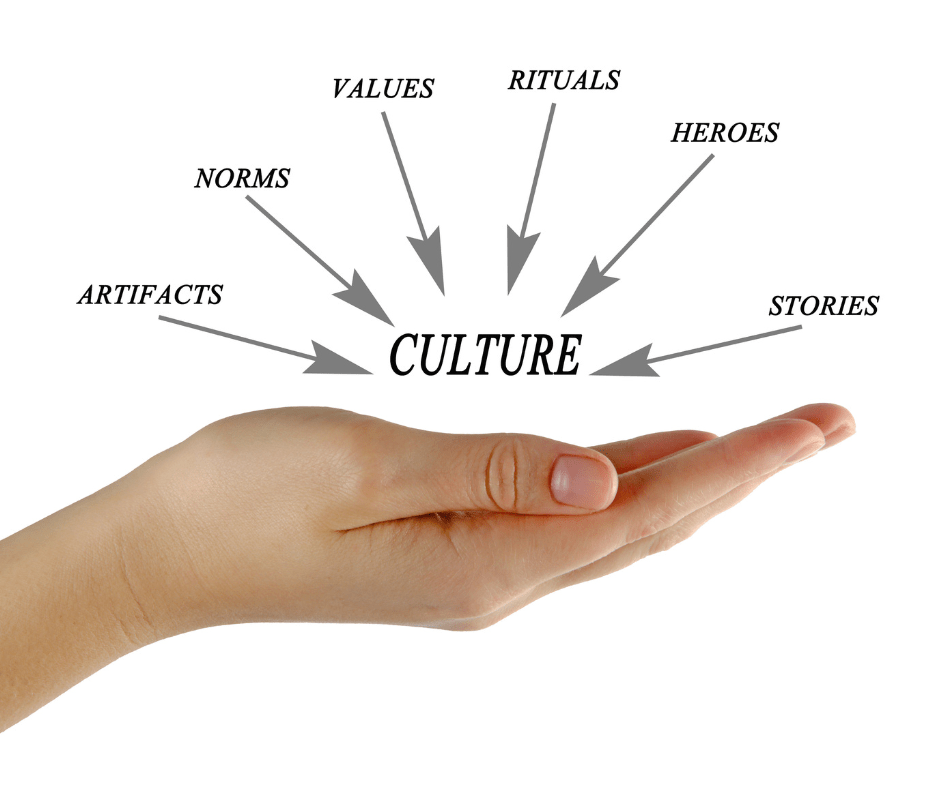

In today’s rapidly shifting business landscape, organizations face a delicate balancing act: how to evolve and innovate while maintaining the cultural DNA that made them successful. This challenge has given rise to a critical leadership competency – cultural stewardship – the art of nurturing organizational heritage while guiding thoughtful transformation.

Today’s article is the final in a 12-part exploration of the Modern Elder’s core competencies distilled from my 40+ year career journey. The topic of understanding of organizational culture and how to preserve valuable traditions while evolving practices is a fitting close to this series.

The Archaeological Approach to Organizational Traditions

Effective cultural stewardship begins with becoming an organizational archaeologist, carefully excavating and examining the traditions, practices, and values that define your company’s identity. Not every long-standing practice deserves preservation simply because it’s old, nor should every new idea be dismissed because it challenges convention.

The most valuable traditions to preserve are those that directly connect to your organization’s core purpose and have demonstrated resilience across multiple challenges. These might include customer service philosophies that have built lasting loyalty, decision-making processes that consistently produce quality outcomes, or mentorship traditions that have developed exceptional talent. Amazon’s customer obsession principle, for instance, has remained constant even as the company has evolved from an online bookstore to a global technology giant.

Look for traditions that embody your organization’s values in action rather than just words on a wall. The weekly town halls where employees can directly question leadership, the informal mentoring relationships that develop organically, or the collaborative problem-solving approaches that emerge during crises – these practices often represent the living essence of your culture.

Orchestrating Cultural Evolution

Healthy cultural evolution requires the same intentionality as biological evolution—it must be adaptive, gradual, and purpose-driven. Organizations that successfully navigate cultural change treat it as an ongoing process rather than a one-time initiative.

The key lies in creating what anthropologists call “cultural bridges” – practices that honor the past while pointing toward the future. When Netflix transitioned from DVD-by-mail to streaming, they maintained their culture of data-driven decision making and customer focus while completely reimagining their business model. The cultural foundation remained solid even as the operational superstructure transformed.

Successful cultural evolution also requires safe spaces for experimentation. Establish pilot programs, innovation labs, or cross-functional teams where new cultural practices can be tested without threatening the entire organizational ecosystem. These experimental zones allow you to observe which changes enhance your culture and which might undermine it.

Building Bridges Across Generational Divides

Perhaps nowhere is cultural stewardship more critical than during leadership transitions and generational handoffs. Institutional memory – the collective knowledge, relationships, and hard-won wisdom that exists in the minds of long-term employees – can evaporate overnight if not carefully preserved and transferred.

Create structured storytelling opportunities where veteran employees can share not just what they know, but how they learned it. The story of how the company navigated the 2008 financial crisis contains more valuable cultural DNA than any policy manual. These narratives help newer employees understand not just the rules, but the reasoning behind them.

Reverse mentoring programs, where younger employees share fresh perspectives with seasoned leaders, create two-way bridges that honor both innovation and experience. When properly structured, these relationships don’t just transfer knowledge – they create hybrid approaches that combine institutional wisdom with contemporary insights.

Cultivating Inclusive Cultural Evolution

True cultural stewardship recognizes that the strongest cultures are those that can incorporate diverse perspectives while maintaining coherent values. This means actively seeking voices that have been historically marginalized and creating pathways for their insights to influence organizational evolution.

Inclusive cultural stewardship goes beyond surface-level diversity initiatives. It involves examining which cultural practices might inadvertently exclude certain groups and being willing to adapt traditions that no longer serve the entire community. The goal isn’t to abandon all traditions, but to ensure that cultural preservation doesn’t become cultural stagnation.

Consider implementing “culture circles” – diverse groups of employees from different levels, departments, and backgrounds who regularly discuss how cultural practices are experienced across the organization. These conversations often reveal blind spots and generate innovative solutions that honor the past while expanding the future.

The Innovation-Tradition Balance

The most successful organizations don’t see innovation and tradition as opposing forces – they view them as complementary aspects of sustainable growth. Apple exemplifies this balance, maintaining Steve Jobs’ design philosophy and attention to detail while continuously pushing technological boundaries.

Establish clear criteria for when to preserve, when to adapt, and when to replace cultural practices. Ask whether a tradition still serves its original purpose, whether it can be modified to work better in current conditions, or whether it has become a barrier to necessary progress.

The Steward’s Legacy

Cultural stewardship isn’t about creating museums – it’s about cultivating living traditions that can adapt and thrive. The most effective cultural stewards understand that their role is temporary; they’re not building monuments to themselves, but creating sustainable systems that will outlast their tenure.

By thoughtfully identifying what to preserve, skillfully facilitating evolution, and courageously bridging divides, cultural stewards ensure that organizations can honor their heritage while boldly embracing their future. In doing so, they create the conditions for sustained success across generations of change.