Recently my wife and I had the great privilege to host the 2023 version of Nina and GrandBob’s Summer Camp – that time when we are able to host our grandchildren at our house or keep grandkids at their parent’s house for an extended time.

For a period of two weeks, we had an amazing time with our nine grandchildren, in two groups as noted in the image above. We laughed, ate ice cream, played games, took walks, and much more. We’re already looking ahead to repeating the camps in 2024!

In reflecting back on those two weeks, I was reminded of the first time we attempted such a thing. It wasn’t hosting our grandkids, their parents were with us, and it wasn’t at our house. But it remains a powerful lesson years later.

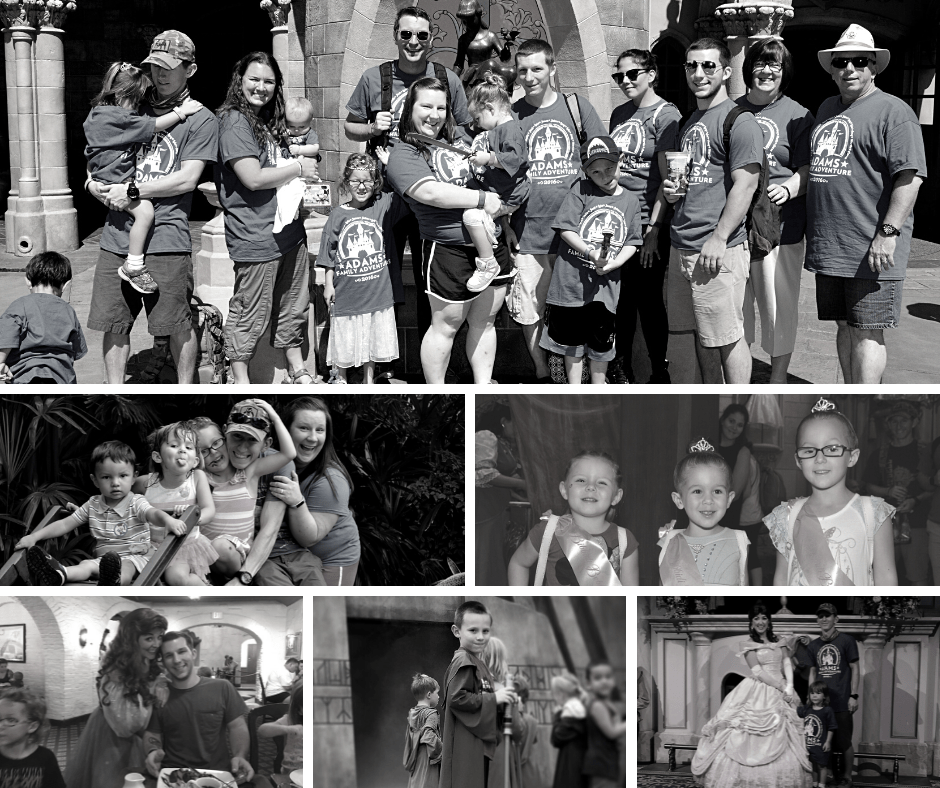

A few years ago, my wife and I had the wonderful opportunity to plan and deliver The Adams Family Adventure – a week-long trip to Walt Disney World for our immediate family of fifteen at the time: six children and nine adults.

All week long I had the most fun watching the rest of the family as they experienced Walt Disney World, most for the first time. We captured that trip in over 3,000 images, to bring up stories in the future from our memory from those images.

As we departed from four different cities on the first day of our trip, we were texting and FaceTiming about our various experiences. It was the first airplane flight for four of the grandchildren (they did great). They left their homes early in the morning, took long flights, got on a big “magical” bus, and arrived at our resort.

To our grandchildren, it must have been a little strange. From the time they came running off the bus, throughout all of the fun adventures of the week, to the goodbyes at the end of the week, they were a little overwhelmed, maybe even overstimulated about the whole process – and I began to see all over again what it means to be curious.

You can, and must, regain your lost curiosity. Learn to see again with eyes undimmed by precedent. – Gary Hamel

My grandchildren’s curiosity was brought sharply into focus when I recently read the following:

In childhood, then, attention is brightened by two features: children’s neophilia (love of new things) and the fact that, as young people, they simply haven’t seen it all before. – Alexandra Horowitz

Alexandra Horowitz’s brilliant On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes shows us how to see the spectacle of the ordinary – to practice, as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle puts it, “the observation of trifles.”

On Looking is structured around a series of eleven walks the author takes, mostly in her Manhattan neighborhood, with experts on a diverse range of subjects, including an urban sociologist, a geologist, a physician, and a sound designer. She also walks with a child and a dog to see the world as they perceive it. What they see, how they see it, and why most of us do not see the same things reveal the startling power of human attention and the cognitive aspects of what it means to be an expert observer.

Here’s an illustrative example as Horowitz walks around the block with a naturalist who informs her she has missed seeing three different groups of birds in the last few minutes of their walk:

How had I missed these birds? It had to do with how I was looking. Part of what restricts us seeing things is that we have an expectation about what we will see, and we are actually perceptually restricted by that perception. In a sense, perception is a lost cousin of attention: both serve to reduce what we need to process of the world “out there.” Attention is the more charismatic member, packaged and sold more effectively, but expectation is also a crucial part of what we see. Together they allow us to be functional, reducing the sensory chaos of the world into unbothersome and understandable units.

Attention and expectation also work together to oblige our missing things right in front of our noses. There is a term for this: inattentional blindness. It is the missing of the literal elephant in the room, despite the overturned armchairs and plate-sized footprints.

Horowitz’s On Looking should be required reading for those wanting to become modern elders. How often do we fly past the fascinating world around us? A world, mind you, that we have been called to serve.

How can we serve others if we aren’t paying attention to the world around us?

To a surprising extent, time spent going to and fro – walking down the street, traveling to work, heading to the store or a child’s school – is unremembered. It is forgotten not because nothing of interest happens. It is forgotten because we failed to pay attention to the journey to begin with.

On Looking, Alexandra Horowitz

The consulting firm I work for uses a thought process called “The Kingdom Concept,” with references to artist Andrew Wyeth:

Most artists look for something fresh to paint; frankly, I find that quite boring. For me it is much more exciting to find fresh meaning in something familiar. – Andrew Wyeth

This reminds me of the concept of vujá dé.

No, that’s not a misspelling – it really is vujá dé – Vujá Dé implies seeing everything as if for the first time or better still, seeing everything everyone else sees, but understanding it differently. (Simon T. Bailey)

You might even say the journey to being a modern elder starts with paying attention – with a healthy dose of vujá dé.

Questions to Ponder

- How do you observe the all-too-familiar in order to discover new meaning and discern the activity of God that others miss?

- What do you look for?

- How can you learn to scrutinize the obvious?

- What does it mean to look for the extraordinary in the ordinary?

A good place to start is paying attention…