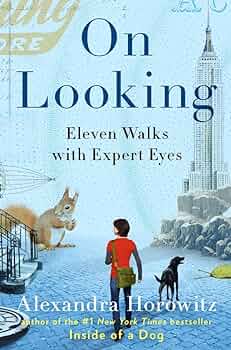

THE QUICK SUMMARY

Alexandra Horowitz shows us how to see the spectacle of the ordinary – to practice, as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle put it, “the observation of trifles.” Structured around a series of eleven walks the author takes, mostly in her Manhattan neighborhood, On Looking features experts on a diverse range of subjects, including an urban sociologist, the well-known artist Maira Kalman, a geologist, a physician, and a sound designer. Horowitz also walks with a child and a dog to see the world as they perceive it. What they see, how they see it, and why most of us do not see the same things reveal the startling power of human attention and the cognitive aspects of what it means to be an expert observer.

Page by page, Horowitz shows how much more there is to see—if only we would really look. Trained as a cognitive scientist, she discovers a feast of fascinating detail, all explained with her generous humor and self-deprecating tone. So turn off the phone and other electronic devices and be in the real world—where strangers communicate by geometry as they walk toward one another, where sounds reveal shadows, where posture can display humility, and the underside of a leaf unveils a Lilliputian universe—where, indeed, there are worlds within worlds within worlds.

A SIMPLE SOLUTION

Paying attention, making a habit of noticing, helps cultivate an original perspective, a distinct point of view. But paying attention isn’t easy.

Rob Walker, The Art of Noticing

Author Rob Walker used the following three quotes spanning over 115 years to remind us that “paying attention” has long been a problem:

- The stimulation of modern life, philosopher Georg Simmel complained in 1903, wears down the senses, leaving us dull, indifferent, and unable to focus on what really matters.

- In the 1950s, writer William Whyte lamented in Life magazine that “billboards, neon signs,” and obnoxious advertising were converting the American landscape into one long roadside distraction.

- “A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention,” economist Herb Simon warned in 1971.

According to Walker, the sense that external forces seek to seize our attention isn’t new – but it feels particularly acute today. Billboards, shop windows, addictive video games, endless news cycles, and commercial appeals tantalize us from all directions. We contend with the myriad distractions flowing through the pocket-sized screens we carry with us everywhere. By various estimates, a typical smartphone owner checks a device 150 times per day – every six minutes – and touches, swipes, or taps it more than 2,500 times.

It would seem that everyone we know or have ever known, every business we’ve ever frequented, every cause we’ve supported or even thought about is demanding to claim attention.

The result is that we no longer know how to “pay attention” – to family, friends, coworkers, and the neighbors next to us.

The capacity to attend is ours; we just forget how to turn it on.

You missed that. Right now, you are missing the vast majority of what is happening around you. You are missing the events unfolding in our body, in the distance, and right in front of you.

By marshaling your attention to these words, helpful framed in a distinct border, you are ignoring an unthinkably large amount of information that continues to bombard all of your senses: the hum of fluorescent lights, the ambient noise in a large room, the places your chair presses against your legs or back, your tongue touching the room of your mouth, the tension you are holding in your shoulders or jaw, the map of the cool and warm places on your body, the constant hum of traffic or a distant lawnmower, the blurred view of your own shoulders or torso in your peripheral vision, a chirp of a bug or whine of a kitchen appliance.

This ignorance is useful: indeed, we compliment it and call it concentration. Our ignorance/concentration enables us to not just notice the scrawls on the page but also to absorb them as intelligible words, phrases, idea.

Alas, we tend to bring this focus to every activity we do – not just the complicated but also the most quotidian.

To a surprising extent, time spent going to and fro – walking down the street, traveling to work, heading to the store or a child’s school – is unremembered. It is forgotten not because nothing of interest happens. It is forgotten because we failed to pay attention to the journey to begin with. On the phone, worrying over dinner, listening to tother or to the to-do lists replaying in our own heads, we miss the world making itself available to be observed.

And we miss the possibility of being surprised by what is hidden in plain sight right in front of us.

Alexandra Horowitz, On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes

A NEXT STEP

There’s no reason to learn how to show you’re paying attention, if you are in fact paying attention.

– Celeste Headlee

Use the following ideas from author Rob Walker as a springboard to becoming known as someone who lives a life of paying attention.

- Seek out strangers

Make it a practice to meet and talk to everyone on your block when you encounter them. Connecting with people is the starting point for building a relationship with them.

- Talk to a stranger

Find small opportunities to begin a conversation by tossing out casual observations about the shared space you’re inhabiting – and give people a chance to fill in their own silences.

- Ask questions – Give compliments

The questions don’t need to be grandiose or existential, just honest expressions of curiosity – which require an alert attentiveness toward other people and what they’re saying or doing that might otherwise slop by unremarked.

When you talk to strangers, you make beautiful and surprising interruptions in the expected narrative of your daily life. You shift perspective.

Kio Stark