As the world prepares for the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics – set to dazzle audiences from February 6-22 with state-of-the-art venues, elaborate ceremonies, and unprecedented media coverage – it’s worth remembering that the spectacular pageantry we’ve come to expect from the Olympic Games didn’t always exist. The template for modern Olympic ceremonies, the marriage of athletics and entertainment, and the very concept of the Games as a televised spectacular all trace back to an unlikely innovator: Walt Disney, and a tiny ski resort in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains that had no business hosting the Olympics.

The story of Walt Disney’s transformative role in the 1960 Winter Olympics has remained largely hidden from popular memory for decades, preserved primarily by dedicated Disney historians who recognized its significance. Jim Korkis, in his meticulously researched volume The Vault of Walt: Still More Unofficial Disney Stories Never Told, Volume 5, has performed invaluable service in documenting this forgotten chapter of both Disney and Olympic history.

Through Korkis’s careful compilation of primary sources, interviews, and historical records, we can now fully appreciate how Disney’s chairmanship of the Pageantry Committee didn’t merely enhance the Squaw Valley Games- it fundamentally reimagined what Olympic ceremonies could be, establishing a template that endures to this day.

Without Korkis’s dedication to preserving these “unofficial” Disney stories, this pivotal moment in entertainment and sports history might have remained buried in archives, its lessons and innovations lost to time. His work ensures that Disney’s Olympic legacy receives the recognition it deserves, illuminating how one man’s vision during a single week in 1960 changed the way the world experiences the Olympic Games forever.

The 1960 Winter Olympics at Squaw Valley marked a watershed moment not just in Olympic history, but in how the world would forever view and experience these quadrennial celebrations. Before Disney’s involvement, Olympic ceremonies were staid, formal affairs. After Squaw Valley, they would never be the same.

The Improbable Dream

When Alexander Cushing, founder of the Squaw Valley Ski Corporation, stunned the sports world in 1955 by securing the bid for the 1960 Winter Olympics, skeptics were everywhere. The location was almost comically unprepared: no mayor, a single chair lift, two tow ropes, and a fifty-room lodge. That was it. Most of the land belonged to Cushing himself, with his former partner Wayne Poulsen owning the rest. As David C. Antonucci details in his comprehensive book Snowball’s Chance: The Story of the 1960 Olympic Winter Games Squaw Valley & Lake Tahoe, the endeavor seemed destined for disaster.

Yet Cushing had a trump card in his bid: Squaw Valley was a blank canvas. Everything could be custom-built for Olympic requirements. Over five frantic years, roads, hotels, restaurants, bridges, ice arenas, speed-skating tracks, ski lifts, and ski-jumping hills materialized from the mountain terrain.

What emerged was more than just infrastructure – it was the largest Winter Olympics ever held to that point, and the first Olympic Games in the United States since 1932. It would also be the first Winter Games nationally televised on CBS (which paid just $50,000 for the rights) and the first to use instant replay technology, though the technique wouldn’t be formally introduced until the 1963 Army-Navy football game.

Enter the Maestro

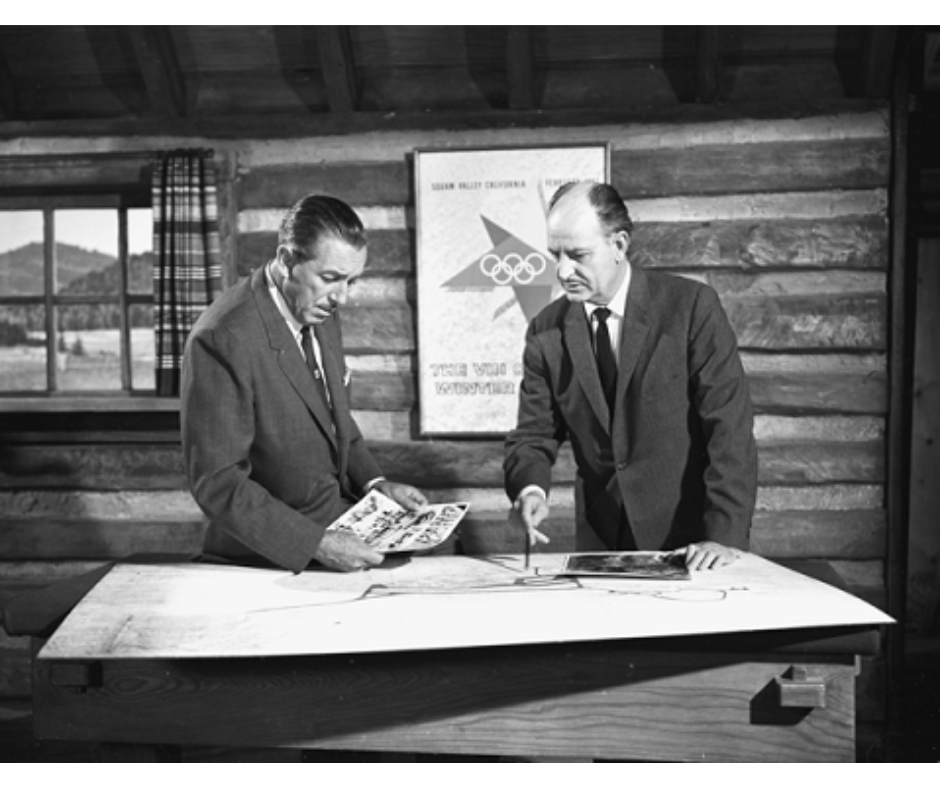

The most crucial decision, however, came when Organizing Committee President Prentis Hale flew to the Disney Studio in Burbank to recruit Walt Disney himself. Hale understood that these Games needed something special – they needed the Disney touch.

Walt accepted enthusiastically. He had been contemplating building a ski resort and saw this as an opportunity for hands-on experience. His involvement extended far beyond a ceremonial role. As Pageantry Committee Chairman, Disney controlled every aspect of the spectacle: opening and closing ceremonies, nighttime entertainment, venue decoration, and even practical matters like tickets, parking, and security.

“Either we’re going to do it the right way or Disney will pull out,” Walt declared when Olympic officials balked at the costs of his elaborate plans. International Olympic Committee Chancellor Otto Mayer initially complained that Disney’s vision had “little to do with the Olympic Spirit” and would turn the event into “another Disneyland.” He changed his tune after the Games, writing to Disney: “Every phase of the Squaw Valley Games was handled magnificently.”

The Disney Machine

Walt assembled his trusted team from Disneyland. Tommy Walker, renowned for Disneyland’s innovative entertainment and fireworks shows, became director of pageantry. Dr. Charles Hirt of USC’s School of Music, who had created the Candlelight Processional for Disneyland, directed high school choruses, recruiting musicians and singers from public schools across California and Nevada. Art Linkletter, who had hosted Disneyland’s televised opening in 1955, became vice-president in charge of entertainment.

The entertainment was unprecedented. Each evening at 8:30 PM in the Olympic Village’s dining center, 1,500 athletes, officials, and reporters enjoyed free performances. Danny Kaye was a sensation on opening night, speaking twelve languages fluently and leading different nationalities in singing “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” in their native tongues. The Golden Horseshoe Revue troupe from Disneyland performed mock gunfights so realistic that security was mistakenly called. Successive nights featured Esther Williams, George Shearing, Red Skelton, Bing Crosby, Jack Benny, and Roy Rogers with Dale Evans.

As Linkletter recalled to Larry King: “We presented shows to all of those athletes. We flew up stars… we put on the greatest shows and I had more fun, and I started to ski then. I was 50 years of age, by the way.”

Disney also arranged for 50 feature films and short subjects to be screened in two specially constructed 100-seat theaters, with free refreshments – another innovation that recognized athletes as whole people needing entertainment and respite.

Imagineering the Olympics

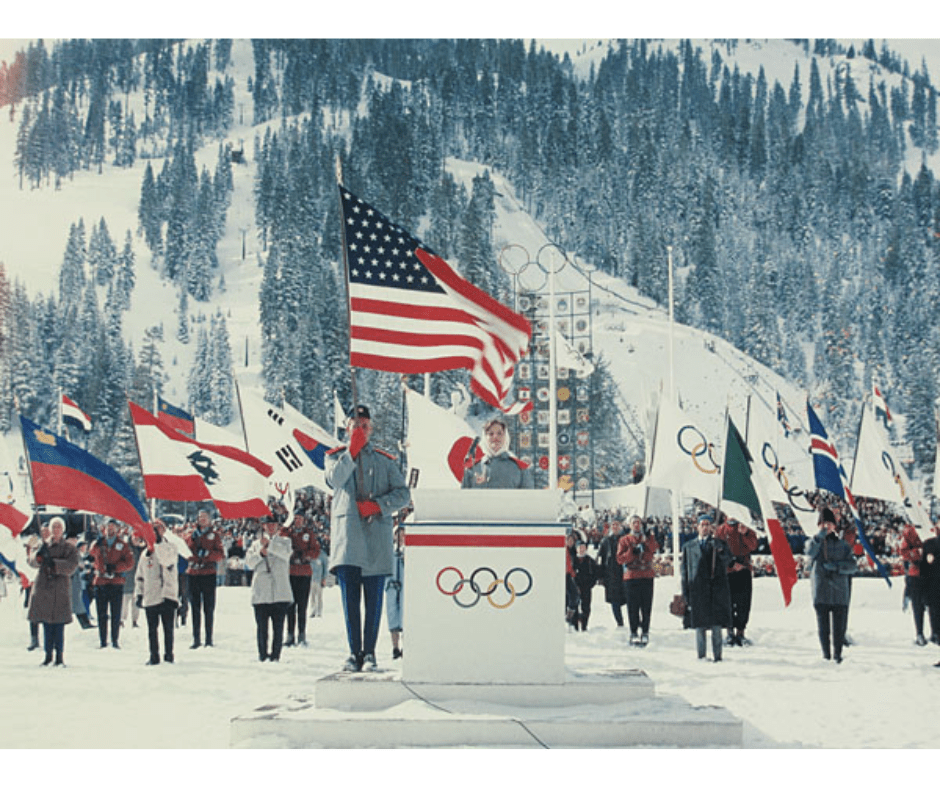

Disney’s most visible contributions came through his Imagineers. John Hench created 32 towering statues – massive figures made of papier-mâché over wire mesh, covered with weather-resistant white stucco to resemble snow. Thirty of these 16-foot sculptures personified Olympic athletes and lined the Avenue of the Athletes. Twenty California and Nevada cities paid $2,000 each to sponsor these statues. Two even larger figures, each 24 feet tall, flanked the centerpiece: the imposing 79-foot Tower of Nations that Hench also designed.

These weren’t temporary props. Several statues remained standing in front of Blyth Arena as late as 1983, when the building’s roof finally collapsed under accumulated snow. Today, the Lake Tahoe museum preserves one of the sculptured heads as a rare surviving artifact.

Hench also redesigned the Olympic Torch itself, making it smaller and easier to carry than previous models, and adding black tape to the shaft for better grip during handoffs. His design influenced torch designs for decades.

Walt conceived the idea of having gleaming aluminum flagpoles for all participating nations – another first. Thirty companies and civic-minded individuals paid $500+ each to sponsor these poles, introducing the concept of official corporate sponsorship to offset Olympic costs. After the Games, sponsors received their flagpoles. One ended up at the Disney Studio commissary. Another went to Walt Disney Elementary School in Marceline, Missouri – the school Walt himself had attended as a child. Each pole bore an engraved plaque stating: “This Olympic flagpole was used at Squaw Valley, California, in the Pageantry ceremonies of the VIII Olympic Winter Games held in February 18-28 1960. Walt Disney (signature), Chairman of Pageantry.”

The Miracle of Squaw Valley

The opening ceremonies on February 18, 1960, would test Disney’s vision like nothing else. Since 6 AM, snow had been falling. By ceremony time, ten inches blanketed the ground. Temperatures dropped to a bone-chilling 10 degrees Fahrenheit. The Olympic Organizing Committee wanted to move everything inside Blyth Arena. Even CBS advised playing it safe.

But moving inside meant abandoning the 1,322 high school band members and 2,328 choir members who had practiced for months and paid their own way to participate. As director Hirt told Walt, there simply wasn’t room for them inside.

It was Walt’s call. Over the loudspeaker, he told everyone to take their positions. He agreed only to a one-hour delay for Vice President Richard Nixon’s late arrival (weather forced Nixon’s motorcade to drive 46 miles through snow instead of helicoptering from Reno).

Then, as Hirt recalled, something miraculous happened: “The clock ticked down to showtime, and, at that moment, the sky parted and the sun shone. It was a miracle. My choir was in front of me. I could see them… And the program went off without a hitch. Then, just at the very close of the final Olympic hymn, the sky covered up again and the blizzard resumed.”

The one-hour ceremony proceeded flawlessly. As 740 athletes paraded in, accompanied by bands and choirs performing “The Parade of the Olympians,” fireworks exploded for each international organization. The Marine Band played. Nixon declared the Games open in approximately fifteen words. Carol Heiss delivered the Olympic Oath. Karl Malden – at the studio filming Disney’s “Pollyanna” – delivered an optional prayer that Walt insisted on including as representing “one of the freedoms of America.”

The ceremony featured the first-ever performance of the original 1896 Olympic hymn (located in Japan and translated from Greek) at a Winter Olympics. Two thousand homing pigeons – standing in for doves that would have frozen – were released from Olympic flag standards. An eight-shot cannon salute marked the eighth Winter Games. The torch arrived via alpine skier Andrea Lawrence and speed skater Ken Henry, who lit the massive Olympic cauldron. As athletes departed, 30,000 helium-filled balloons ascended into the sky alongside the first-ever daytime fireworks display and 100 unfurled Olympic flags.

As if on cue, within five minutes of the ceremony’s conclusion, the snowstorm resumed with greater fury, forcing officials to postpone the next day’s downhill event. A local commentator marveled at “the split-second timing of a well-rehearsed stage show.” One Russian delegation member reportedly tried to grill security guards about what chemicals were used to stop the snow for an hour.

United Press International noted that the Russian delegation “sat impassively through the entire event” due to Cold War tensions – until Disney’s fireworks finale, when they “excitedly clapped each other on the shoulders and their faces were swathed with grins.”

The Lasting Legacy

Life magazine declared in its March 7, 1960, issue: “Greatest winter show on earth. The overall impression that Americans and visitors alike took home was that the 1960 Winter Olympics had been the most efficient and enjoyable ever.” Los Angeles Times reporter Braven Dyer wrote: “The opening ceremony was the most remarkable thing I ever saw. No matter how much credit you give Walt Disney and his organization, it isn’t nearly enough.”

What Walt Disney accomplished at Squaw Valley fundamentally transformed Olympic pageantry. Before 1960, opening ceremonies were perfunctory affairs. After Disney, they became spectacular productions that rivaled the athletic competitions themselves. The integration of entertainment, the emphasis on creating lasting goodwill, the attention to both grand gestures and practical details, the use of innovative technology, the concept of corporate sponsorship – all of these became Olympic standards.

Card Walker, Disney’s director of publicity at Squaw Valley, later became chairman of the Disney company and served on the Executive Committee of the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee, where he was instrumental in designing the official mascot (Sam the Eagle) for the 1984 Games and drew up preliminary plans for those opening and closing ceremonies.

The influence extended beyond pageantry. Disney’s insistence on treating security with a light touch – doing it the “Disney way” so it was effective but not heavy-handed – introduced a new approach to managing massive public events. His integration of entertainment for athletes recognized them as whole people, not just competitors. His commitment to including young people in the ceremonies, even when weather threatened their participation, reflected his belief in “the spirit of American youth.”

As author Antonucci documents in Snowball’s Chance, the 1960 Winter Olympics transformed from an improbable dream at an obscure ski resort into a wildly successful event that “put the ‘New West’ on the map and brought our region into the public consciousness as a winter resort destination.”

Full Circle

When the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics open on February 6 at Milan’s San Siro Stadium – featuring performances by Mariah Carey, Laura Pausini, and Andrea Bocelli, with elaborate ceremonies produced by professional entertainment companies – organizers will be following a blueprint written 66 years ago in the California mountains.

The spectacle we now take for granted, the seamless integration of athletics and entertainment, the emphasis on creating memorable experiences for athletes and spectators alike – all of this can be traced back to one week in February 1960, when Walt Disney looked at a snowstorm, refused to compromise his vision, and somehow made the sun shine on command.

As Olympic Games have grown into multi-billion-dollar spectacles hosted in the world’s grandest cities, it’s worth remembering that the foundation of modern Olympic pageantry was laid not by international sports committees or entertainment conglomerates, but by a single creative visionary who understood that sports, like storytelling, are most powerful when they touch the heart as well as inspire the mind.

The Milano Cortina Games will undoubtedly be spectacular. They will feature cutting-edge technology, massive budgets, and professional production values that would have seemed like science fiction in 1960. But they will also owe a debt to an obscure ski resort, a determined developer with an impossible dream, and Walt Disney’s unwavering belief that even the Olympics deserve a touch of magic.

That’s a legacy worth remembering as we marvel at the spectacles to come – and a reminder that sometimes the most lasting innovations come from the most unexpected places, built by dreamers who refuse to play it safe when the snow starts falling.

Photo Credits: Walt Disney Family Museum, William S. Young

Part of a regular series on 27gen, entitled Wednesday Weekly Reader.

During my elementary school years one of the things I looked forward to the most was the delivery of “My Weekly Reader,” a weekly educational magazine designed for children and containing news-based current events.

It became a regular part of my love for reading, and helped develop my curiosity about the world around us.