Nationwide, more and more entrepreneurs are committing themselves to creating and running “third places,” also known as “great good places.”

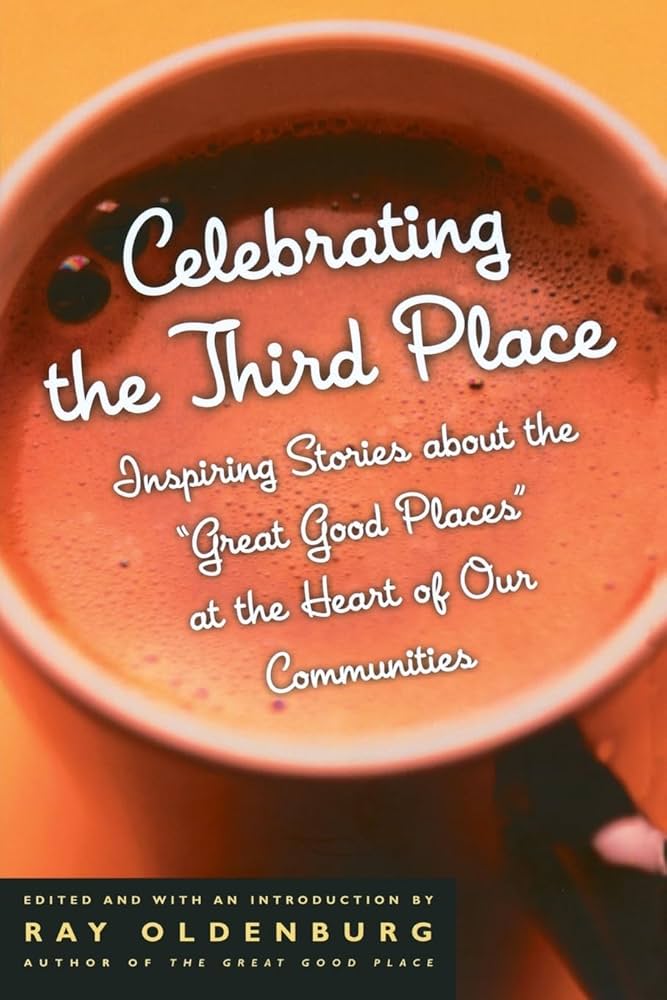

In his landmark work, The Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg identified, portrayed, and promoted those third places. Ten years after the original publication of that book, Oldenburg wanted to celebrate the many third places that dot the American landscape and foster civic life.

Celebrating the Third Place brings together fifteen firsthand accounts by proprietors of third places, as well as appreciations by fans who have made spending time at these hangouts a regular part of their lives. Among the establishments profiled are a shopping center in Seattle, a three-hundred-year-old tavern in Washington, D.C., a garden shop in Amherst, Massachusetts, a coffeehouse in Raleigh, North Carolina, a bookstore in Traverse City, Michigan, and a restaurant in San Francisco.

Ray Oldenburg’s Celebrating the Third Place (2000) builds upon the ideas introduced in his earlier work, The Great Good Place (1989), and refines the concept of third places. While The Great Good Place laid the theoretical groundwork for understanding the importance of informal gathering spaces in fostering community, Celebrating the Third Place offers a more practical examination of these spaces. Through real-world examples and case studies, Oldenburg highlights how third places function in various cultural contexts and emphasizes their potential to revitalize and strengthen communities. This article will explore how it refines the concept of third places, and discuss its continuing impact on urban planning, social sciences, and community development.

In the aftermath of World War II, a significant shift occurred in American urban landscapes, dramatically impacting the existence and survival of “third places” – those informal public gathering spaces essential for community building. These places, often locally owned, independent, and small-scale businesses, have faced increasing challenges due to changing urban planning paradigms, economic pressures, and evolving social habits.

The Rise of Chains and Unifunctional Zoning

One of the primary culprits in the decline of third places has been the emergence of chain establishments, coinciding with the implementation of unifunctional zoning policies. This zoning approach, which separates residential areas from commercial ones, has forced Americans to rely heavily on cars for even the most basic errands. As a result, people now drive to strips and malls where only large chains can afford to operate, effectively squeezing out smaller, local businesses.

Before the advent of unifunctional zoning, communities were designed with a mix of residential and commercial spaces. Small stores, taverns, offices, and eateries were within walking distance for most town and city dwellers, forming the backbone of community life. These businesses typically served customers within a two or three-block radius and thrived in this localized ecosystem. However, the introduction of negative zoning created an environment where impersonal chain operations could flourish at the expense of independent establishments.

The Human Element: Public Characters vs. Corporate Policies

The shift from local independents to chain establishments has had profound implications for community dynamics. Many operators of mom-and-pop stores were what Jane Jacobs called “public characters” – individuals who knew and cared about everyone in the neighborhood. These figures played crucial roles in maintaining community cohesion, keeping an eye on children, monitoring neighborhood safety, and facilitating the flow of important local information.

In stark contrast, chain establishments often prioritize efficiency and standardization over community engagement. High employee turnover rates and corporate policies discouraging casual interactions with customers have eroded the personal connections that once defined local businesses. This shift has resulted in a less personalized, less engaged community experience.

Urban Planning and the Retreat to Private Spaces

Decades of poor urban planning have further exacerbated the challenges faced by third places. The public sphere has become increasingly inhospitable and difficult to navigate, encouraging a trend towards “nesting” or “cocooning” – the tendency for people to retreat to the comfort of their private homes. As homes have become better equipped, more comfortable, and more entertaining, the appeal of venturing out into public spaces has diminished.

This domestic retreat presents a significant challenge to movements like Traditional Town Planning or the New Urbanism, which aim to restore community and public life through architectural and layout principles reminiscent of the 1920s. However, the effectiveness of these approaches in isolation is questionable. Examples of well-designed public spaces failing to attract people suggest that architectural solutions alone may not be sufficient to revitalize community life.

The Digital Age and Its Impact

The rise of personal computers and internet connectivity has further complicated efforts to promote public life. Many people now spend significant time online, whether for work, entertainment, or social interaction. This digital engagement often comes at the expense of face-to-face community interactions, presenting yet another obstacle to the revival of third places.

Hope for Revival: The Harrisburg Example

Despite these challenges, there are examples of successful efforts to revitalize public life and support third places. The city of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, offers an inspiring case study. Following years of economic stagnation and natural disasters, Harrisburg embarked on a concerted effort to promote community spirit and street life.

Key to Harrisburg’s success was the city government’s supportive approach to new, independent businesses. By recognizing and rewarding establishments that contributed to the city’s betterment, Harrisburg created a welcoming environment for entrepreneurs and community builders. This approach, combined with the preservation of walkable, human-scale architecture and mixed land use, has resulted in a vibrant public life that larger cities might envy.

The Loss of Community Time

A final consideration in the struggle for third places is the loss of what could be called “community time.” The replacement of a post-work free hour with commuting time has had a significant impact on community cohesion. Where people once had time to engage with their community before returning home, they now often spend that time isolated in their cars, fostering frustration rather than connection.

The challenges facing third places in modern America are numerous and complex, ranging from urban planning decisions to economic pressures and changing social habits. However, the importance of these spaces for community building and social cohesion remains as vital as ever. Success stories like Harrisburg demonstrate that with intentional effort and supportive policies, it is possible to create and maintain vibrant third places.

As we move forward, it is crucial to recognize the value of these spaces and work towards creating environments that foster their development. This may require rethinking our approach to urban planning, supporting local businesses, and actively encouraging community engagement. By doing so, we can hope to preserve and revitalize the “stuff of community” that third places provide, enriching our social fabric and improving the quality of life in our towns and cities.